Let’s start with a basic definition of equity: Equity is the most basic form of ownership in a company. Since virtually all private equity-backed companies in the United States are corporations, we are going to focus on equity in a corporation.

|

Private equity, generally speaking, is an equity (stock) investment in a privately-held company. My blog post “LP Corner: What is Private Equity?” provides an overview of how the term “private equity” is used. This post is going to explore the “equity” component of “Private Equity.” This post is a complement to my posts "LP Corner: What is Private Equity" and "LP Corner: The "Private" in Private Equity".

Let’s start with a basic definition of equity: Equity is the most basic form of ownership in a company. Since virtually all private equity-backed companies in the United States are corporations, we are going to focus on equity in a corporation.

0 Comments

To all readers: I hope you and your families are healthy and safe. My thoughts are with all who are impacted by this deadly virus.

I’ve been around for a while, and have experienced several market dislocations in my career. I had just started my career as a corporate finance attorney when the “Black Monday” stock market crash of October 19, 1987 occurred. I was a telecommunications investment banker when the dot-com crash occurred in March 2000. I was a private equity fund-of-funds manager when the Global Financial Crisis (“GFC”) hit in 2008. Because of these experiences, I have some thoughts for limited partners (“LPs”) during this crisis. Overview

Private equity funds-of-funds (“FOFs”) are funds that invest in other private equity funds, which then invest directly into privately-held companies. By investing in a FOF, a limited partner (“LP”) obtains a diversified portfolio of private equity fund investments as well as a larger portfolio of indirect investments in underlying private companies. I have worked for two private equity fund-of-fund managers and understand well the pros and cons of these vehicles. This post provides an overview of FOFs. Structure FOFs invest in a portfolio of private equity funds (known as “portfolio funds”), which in turn invest in privately-held companies (known as “underlying portfolio companies”). A FOF will invest in a portfolio of private equity funds and each portfolio fund will invest in a portfolio of private companies. As a result, an LP’s single investment in a FOF can provide the LP with exposure to many funds and potentially hundreds of underlying portfolio companies. The simplified diagram below illustrates this. Venture capital is a competitive business. There are roughly a thousand venture capital firms in the US, all vying to find the next runaway smash hit of a startup. It all starts with deal flow. Generating high quality deal flow is paramount to a successful investing strategy. So how do venture capitalists (“VCs”) source their deals? That’s the topic of this post.

Just as wines have “vintage years”, private equity funds also have "vintage years." But what is a vintage year? For wine, it’s universally recognized as the year the grapes were harvested. However, it’s not that simple for private equity, as various industry participants define “vintage year” differently.

Consider the following hypothetical: In 2011, two private equity professionals decide to raise a fund. That year they form a legal entity for the fund and launch their fundraising efforts. In late 2012 the fund has its initial closing of commitments from limited partners, and makes its first capital call, where limited partners make their first cash contribution to the fund. In 2013, the fund makes its first investment. In 2014, the fund has its final closing. As of September 30, 2018, the fund has a net IRR of 18.5%. What should the vintage year be for this fund - 2011, 2012, 2013 or 2014? To read more, please click on "Read More" below. An important event in the life of a private equity fund is when the fund “exits” its investment in a portfolio company. An exit is also known as the time when a fund “cashes out” or “liquidates” its investment in a portfolio company. Exits occur in three main ways: (1) the portfolio company is sold and the fund receives cash or publicly-traded securities for its shares in the portfolio company; (2) the portfolio company holds its initial public offering, or IPO, and the fund later sells its shares in the portfolio company on the public market or the fund distributes the publicly-traded shares to the fund’s limited partners; and (3) the fund sells its shares of a portfolio company to another investor in a private transaction (this is known as a direct secondary sale). While there are other ways a fund can achieve a full or partial exit, the above exit routes are the main ways a fund achieves liquidity.

We have discussed IPOs in prior posts (see for example: LP Corner: What LPs Need to Know About IPOs). In this post, we will discuss some of the things about the sale of a portfolio company that LPs should know. Common M&A structures. The sale of a company can take many different forms. The most common sale structures are:

To read more, please click on "Read More" below. Why is it that mutual funds take an investor’s capital on day 1, while PE funds take an investor’s capital over time? That’s the topic of this post.

When an investor makes an investment in a mutual fund, the investor invests the entire amount of the investment on day 1. The mutual fund manager will quickly use this money to increase existing positions in the fund or make new investments. It’s easy for the mutual fund manager to put the money to work by buying publicly-traded securities. Investments in private equity funds are different. Private equity funds operate on a “called capital” model. By way of background, when an investor (known as a “limited partner” or “LP”) makes a legal commitment to a private equity fund, the LP commits to providing the fund with a certain maximum investment amount, which is known as the “LP commitment.” For example, if an LP agrees to invest a total of $10 million in a private equity fund, that $10 million is the LP commitment. For more background, please see the following posts:

To read more, please click “Read More” below. Show me the money!

When a company holds its initial public offering, or IPO, some will call the IPO the “initial profit opportunity” as it can be an opportunity for pre-IPO investors to sell their stock and generate significant profits. This post will discuss what investors in private equity funds need to know about IPOs. To read more, please click “Read More” below. Sit right back and you’ll hear a tale…

In this fictional account, Able Bentley Capital is a $500 million private equity fund (“ABC”). ABC is formed as a Delaware limited partnership, and the general partner (“GP”) is ABC Partners. (For a discussion of limited partnerships, see my post “LP Corner: US Private Equity Fund Structure - The Limited Partnership.”) ABC makes a number of international investments. Bill Smith is one of managing partners of the management company and a member of the GP. Bill sources and leads several international investments. It is common in international investments to have the fund’s investment flow through one or more intermediate (known as “blocker”) shell companies in order to shield the fund from negative tax consequences. Using a complicated blocker structure, Bill was able to defraud ABC out of several million dollars. The fraud was eventually discovered and after several years Bill was convicted of fraud and embezzlement. Situations where a GP (or a principal of the GP or management company) behave truly badly are rare, but they do occur. The question becomes, what should happen when really bad behavior occurs? Read on to find out! To read more, please click “Read More” below. Divorce, Private Equity style...

Private equity funds have long lives. Private equity limited partnership agreements (LPAs) typically provide for an initial 10-year term, plus two one-year extensions at the discretion of the general partner of the fund (GP). However, fund terms often stretch out for much longer, sometimes 15 to 18 to 20 or more years. This is truly a long-term commitment, for both the limited partners (LPs) and for the GP. For an overview of LPs, GPs and limited partnerships, please see my prior post "LP Corner: US Private Equity Fund Structure - The Limited Partnership." Because funds stay around for a long time, things will change. Partners may leave the fund’s management company; the investment strategy might drift away from the initial strategy; the investment performance may be terrible to the point that the LPs want to stop the GP from investing; the fund or management firm may be embroiled in a scandal; or in rare cases, the GP may behave badly (not illegally or in violation of the LPA, but in ways that may place their personal interests above the best interests of the LPs). There are many other changes that can occur during the life of a fund. To read more, please click "Read More" to the right below. This is one of a series of posts on fund terms. Other posts in this series include:

When an LP invests in a fund, it is because the LP believes that the investment team will successfully invest the fund. But what happens if members of that investment team leave the firm in the midst of investing? What happens if a key member of the team dies, or is convicted of securities fraud? A “key person” clause (historically known as a “key man” clause) provides LPs with protections in case these events, and others, occur. To read more, please click on the "Read More" link below and to the right. Why is it that most buyout funds, many growth equity funds and few venture capital funds have an 8% preferred return hurdle? Why should there be a difference among the different strategies?

What is a preferred return hurdle? A preferred return hurdle is a component of the fund manager’s carried interest. To read more, please click on the "Read More" link below and to the right. This is one of a series of posts on fund terms. Other posts include:

A private equity fund can generate fees in certain situations that are separate and distinct from management fees. These situations include: To read more, please click on the "Read More" link below and to the right. This is one of a series of posts on fund terms. Other posts include:

In this post, we will explore what happens if the GP is paid too much carry. Generally speaking, the GP must return the overpayment, and this is called the GP clawback. But it’s not that simple, so read on! How a GP Can be Paid Too Much Carry In the prior post “LP Corner: Fund Terms – Carried Interest Overview” we discussed that there are two main types of carried interest – whole fund carry (also known as “European carry”) and deal-by-deal carry (also known as “American carry”). In whole fund carry, the GP is paid carry only after the fund has returned to the LPs all of their contributed capital. This has the effect that the GP is paid carry later in the fund’s life (compared to deal-by-deal carry), and because the LPs are repaid all of their contributed capital before the GP takes its carry, it is pretty unlikely that the GP will receive too much carry. Conversely, in deal-by-deal carry, the GP can collect carry much earlier than under whole fund carry, and in some cases, the GP can be paid too much carry over the life of the fund. Please review the example in the prior post for more detail on this and to see how too much carry can be paid. To read more, please click on the "Read More" link below and to the right. This is one of a series of posts on fund terms. Other posts include:

In this post, we will explore two items relating to carried interest: preferred return and GP catchup. Preferred Return Hurdle A preferred return (or “hurdle rate”) is a minimum threshold return that LPs must receive before the GP can receive its carried interest (or “carry”). The preferred return is usually expressed as a percentage return per year, and in private equity that is usually 8% per year. This means that the LPs must receive an 8% annual return on their contributed capital before the GP can receive carry. GP Catchup There are two types of preferred return hurdles: (1) a “pure preferred return” (also known as “hard preferred return”); and (2) a preferred return with GP catchup. Pure Preferred Return Hurdle. In the pure preferred return hurdle, the GP only receives carry on gain in excess of the preferred return hurdle. This has the impact of reducing the carry the GP receives over the life of the fund. The pure preferred return hurdle is not used in private equity. Preferred Return with GP Catchup. In a preferred return with GP catchup, once the preferred return hurdle is met, the GP receives all or most of the future profits until the GP catches up to its 20% carry amount, and after that the profits are split 80% to the LPs and 20% to the GP (for its normal carry). The preferred return with GP catchup results in the GP receiving its entire 20% profit share. This version of preferred return hurdle is the norm in the private equity industry. To read more, please click on the "Read More" link below and to the right. This is one of a series of posts on fund terms. Other posts include:

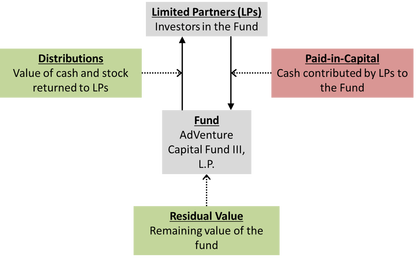

Carried Interest Overview As discussed in my prior post on management fee, the long-standing fee model for private equity funds has been a “2 and 20” model, referring to a 2% management fee and a 20% carried interest. But what is this “carried interest?” Read on! Carried interest, also known as “carry,” “profit participation,” “promote” or the "distribution waterfall," is the share of the fund’s profit the fund’s manager (also known as “general partner” or “GP”) earns if the fund returns a profit to the fund’s investors (also known as “limited partners” or “LPs”). See my prior post "LP Corner: US Private Equity Fund Structure - The Limited Partnership" for more detailed descriptions of LPs and the GP. When a private equity fund calls capital from its LP investors (this is known as “paid-in-capital’ or “called capital” - see my prior post "LP Corner: On Committed Capital, Called Capital and Uncalled Capital" for further discussion of this topic), the GP manager of the fund will use that capital to make investments and to pay for fund expenses, such as management fee. When the investments are realized, the amount in excess of the original investment amount is profit. The Two types of Carry: Whole Fund and Deal-by-Deal There are two main types of carry: whole fund carry and deal-by-deal carry. To read more, please click on the "Read More" link below and to the right. This is one of a series of posts on fund terms. Other posts include:

In private equity, the term “2 and 20” refers to the traditional compensation structure for private equity funds: 2% management fee and 20% performance fee (also known as “carried interest” or “carry”). In this post, we will explore management fee. Historically, management fee was intended to provide fund managers with enough money to pay modest salaries, rent modest offices and incur modest expenses. It was said that management fee was intended to let the fund manager “keep the lights on” and that the performance fee (known as “carried interest” or “carry”) was where the fund manager made its money. While investors in private equity funds (known as “limited partners” or “LPs”) continue to take this view, terms in fund documents (known as the "limited partnership agreement" or "LPA") relating to management fee have become more complex. Let’s dig in. In previous posts, we have explored committed capital and the investment period:

We will look at management fee in three phases of a fund’s life: the investment period, the harvesting (or realization) period and during extensions. To read more, please click on the "Read More" link below and to the right. I have clients who are new to investing in private equity, and one of the first conversations we have is about "what is private equity"?

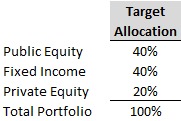

Private equity, generally speaking, is an equity (stock) investment in a privately-held company. Private = privately held company. Equity = stock. It's a little more complicated than that, but that's a useful starting point. The denominator effect refers to an investor's private equity portfolio value exceeding its target allocation due to the decline in value of other elements in the investor's overall investment portfolio. Conversely, the “reverse denominator effect” refers to private equity value falling below its target allocation due to the increase in value of other elements in the portfolio. In order to understand Denominator Effect and the Reverse Denominator Effect, this post will first review basic portfolio allocation and rebalancing, and then will briefly review fractions. Portfolio Allocations and Rebalancing Most investors will develop a portfolio investment strategy by allocating a portion of the portfolio to different investment classes (called “asset classes”) such as public equities (stocks), fixed income securities (bonds), real estate, cash and private equity. Investors may define asset classes differently and may allocate their portfolio across asset classes differently. Let’s say an investor has $1 billion to invest. After working with their investment advisor, they have decided to create target allocations for their portfolio as follows: 40% to public equities, 40% to fixed income and 20% to private equity. (We’re keeping it simple here; most investors will allocate to more than 3 asset classes). These are target allocations – the actual values may vary from the target value. The target allocation will look like this: To read more, please click on "Read More" link below.

,This one of a series of posts on fund performance metrics. Other posts in this series include:

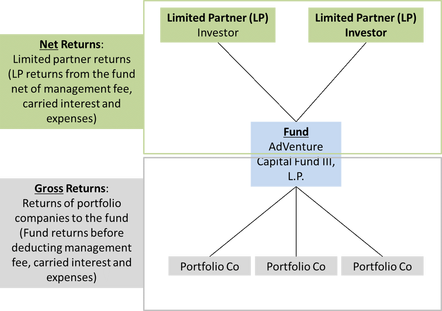

We have discussed how to evaluate fund performance, but a common area of confusion is gross returns versus net returns. I briefly introduced this topic in LP Corner: Private Equity Fund Performance - An Overview, and this post expands on that introduction. When talking returns in private equity, it is very important to know what kind of returns you are discussing: gross or net returns. The difference between these two metrics can be meaningful, and so it is important to know what is being discussed. Gross returns, simply stated, are the returns a fund obtains from its investments, without deducting any management fees, fund expenses or carried interest. Net returns are the returns a limited partner (LP) receives from the fund, after deduction of all management fees, fund expenses and carried interest. LPs are about net returns, as net returns are the real returns an LP receives from its investment in a fund. When we talk about gross vs net returns, it can apply to gross vs net IRRs or gross vs net TVPI multiple. The graphic below shows the difference between gross and net returns for a fund. LPs invest in a fund. The fund invests in portfolio companies. Gross Returns are the returns the fund obtains from its investments in portfolio companies. Gross Returns are before deducting management fee, fund expenses and carried interest. Once the fund does deduct the management fee, fund expenses and carried interest, the return the LPs obtain from the fund are the Net Returns. To read more, please click on "Read More" link below.

This one of a series of posts on fund performance metrics. Other posts in this series include:

We have now discussed the three metrics that are primarily used to evaluate the performance of private equity funds: (1) the multiples TVPI, DPI and RVPI; (2) IRR; and (3) PME. We will now discuss how to use these metrics to evaluate the performance of private equity funds. Overview There are several ways to evaluate the performance of a fund, or a portfolio of funds, with the main methods being:

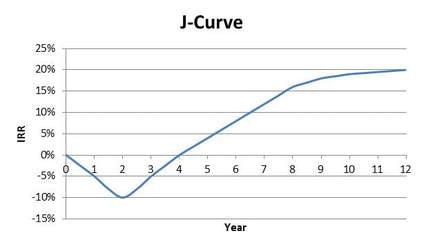

Absolute Return Absolute return refers to a specific threshold requirement for a fund’s performance. For example, some LPs may say that they expect a 3.0x TVPI and 30% IRR net return from early stage venture capital funds, or a 2.0x and 20% return for buyout funds. If a fund’s return exceeds these metrics, then it “outperforms” the metrics. If a fund’s returns are less than these metrics, then the fund “underperforms.” A note about absolute return. Most funds experience a J-Curve, where performance declines in the first couple of years of a fund when fund expenses and investment losses exceed investment gains, but the fund’s performance improves over the next several years. The J-Curve is more pronounced for early-stage venture capital funds. The J-Curve looks something like this: For more on the J-Curve, see my post: “LP Corner: The J-Curve.”

The point here is that using absolute returns are really only useful late in a fund’s life or after the fund is liquidated. If one were to apply a 20% absolute return metric to the fund in the J-Curve example above, the fund would underperform all years until the last year in the graph. To read more, please click "Read More" to the right below. This one of a series of posts on fund performance metrics. Other posts in this series include:

We have now discussed two of the three primary metrics uses to evaluate the performance of private equity funds: (1) the multiples TVPI, DPI and RVPI; and (2) IRR. We will now explore the third primary metric: Public Market Equivalent, or PME. Overview Broadly speaking, PME is a return metric that compares the return of a private equity fund (or a portfolio of funds) to the hypothetical return of a chosen public stock market index, such as the S&P 500 or Nasdaq, using the cash flows as the fund as a basis for investment in the stock market index. For example, a fund may have an IRR of 15%, while the PME obtained using the S&P 500 as the index is 10%, suggesting that the fund has outperformed the S&P 500 by 500 basis points (bps). There are several variations of PME, but these are commonly used:

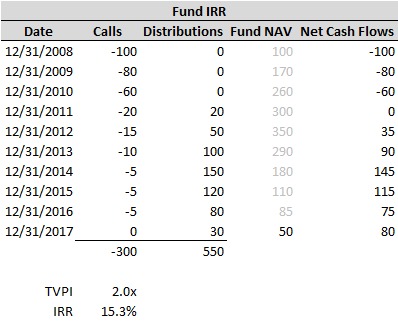

LN PME The LN PME (also known as the Index Comparison Method or ICM) is widely considered the “first” PME approach (and it is often referred to simply as “PME”). The LN PME matches each contribution and distribution of a fund with a hypothetical purchase and sale of a reference public market index, such as the S&P 500. The residual value of the fund is not matched to the LN PME; rather, the LN PME residual value is based on the performance of the hypothetical invested capital in the index. With these cash flows, an LN PME return for the public market index is compared directly against the IRR for the fund. If the fund’s IRR exceeds the LN PME, then the fund has outperformed the public market index. If the LN PME IRR exceeds the fund’s IRR, then the fund has underperformed the public market index. Note that the IRR generated using LN PME isn’t a “real” IRR – it’s an estimation because of the manipulation of the residual value. One nice thing about the LN PME is that it is conceptually straightforward. However, the mechanics of LN PME have some issues. One issue for the LN PME approach is that the residual value for the PME index can be negative. This can occur if the fund has distributions early in the life of the fund, or has a series of large distributions late in the life of the fund. The problem is that a fund can’t have a negative residual value (technically a fund could have a negative residual value, but it would be a very rare case). As a result, LN PME isn’t used very often in private equity. The other forms of PME attempt to address the drawbacks of the LN PME. Let’s look at an example: First consider the fund that we want to evaluate. The fund is presented below: To read more, please click on "Read More" to the right below.

This one of a series of posts on fund performance metrics. Other posts in this series include:

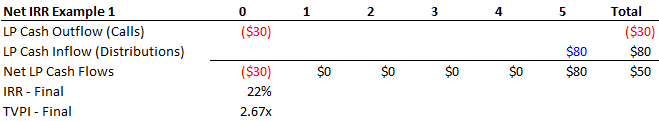

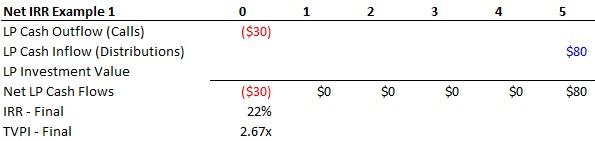

In this post, we will explore internal rate of return (IRR) as a tool for evaluating fund performance metrics. Recap In my prior post, we discussed the basics of IRR in a fund context. In this post, we build on that to explore what happens year by year for that fund. In Example 1 in the last post, we introduced a fund, where the LP paid $30 million to the fund in a capital call at time = 0 and received $80 million back from the fund (as distributions) at the end of year 5. These simple cash flows yielded an IRR of 22% and a TVPI of 2.67x.  To read more, please click on "Read More" to the right below.

This one of a series of posts on fund performance metrics. Other posts in this series include:

In this post and the next post, we will explore measuring fund performance using internal rate of return or IRR. This post will provide an overview of IRR. If you already have a good grasp of IRR, you can move to part two of this series: LP Corner: Fund Performance Metrics - Internal Rate of Return (IRR) - Part Two. IRR Overview In a basic sense, IRR is the return from a series of cash flows over time. In the Private Equity space, IRR is commonly used to evaluate the performance of private equity (including venture capital, growth equity and buyout) funds. IRR is best calculated using Excel, Google Sheets or another financial spreadsheet program. Simple IRR Examples Let’s assume that an LP commits $30 million to a fund, and that the fund returns $80 million in distributions to the LP. (For a discussion on committed capital, see "LP Corner: On Committed Capital, Called Capital and Uncalled Capital.") On a multiple basis, this equates to a Total Value to Paid-in-Capital (TVPI) of 2.67x ($80M / $30M) – which sounds pretty good. But let’s explore a bit deeper. Note that in these examples, we are looking at cash flows from the perspective of an LP - payments made by the LP and money received by the LP. This is known as a "Net IRR" because it focuses on the cash flows to and from the LP. For a discussion of gross vs net returns, see "LP corner: Private Equity Fund Performance - An Overview." Example 1: Assume that when the fund has its closing (which is time 0 for purposes of calculating the IRR in Excel), it calls all capital from the LP (in reality, this doesn’t happen, but humor me as this is an example). In five years, the fund distributes $80 to the LP. This looks like this: To read more, please click on "Read More" to the right below. This one of a series of posts on fund performance metrics. Other posts in this series include:

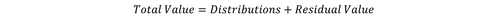

In this post, we will explore using multiples as a tool to evaluate fund performance. The multiples are:

Here’s some important terminology that will help explain the multiples:

To better understand the above terminology, let’s look at the terms graphically: To read more, please click "Read More" to the right below.

|

About this Blog

This Blog is a collection of thoughts on a variety of topics of interest to me, including: Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

Copyright Notice:

All original works on this site are © Allen J. Latta. All rights reserved. Neither this website nor any portion thereof may be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express prior written permission of Allen J. Latta. LP Corner® is a registered trademark of Campton Private Equity Advisors. Used with permission. DISCLAIMER: Readers of this Blog are not to construe it as investment, legal, accounting or tax advice, and it is not intended to provide the basis for the evaluation of any investment. Readers should consult with their own investment, legal, accounting, tax and other advisors to the determine the benefits and risks of any investment.

Private equity investments involve significant risks, including the loss of the entire investment. This Blog does not constitute an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy any security. |