We have discussed IPOs in prior posts (see for example: LP Corner: What LPs Need to Know About IPOs). In this post, we will discuss some of the things about the sale of a portfolio company that LPs should know.

Common M&A structures.

The sale of a company can take many different forms. The most common sale structures are:

- Stock for Cash

- Stock for publicly-traded stock

- Stock for privately-traded stock

- Asset sales

- Mergers

To read more, please click on "Read More" below.

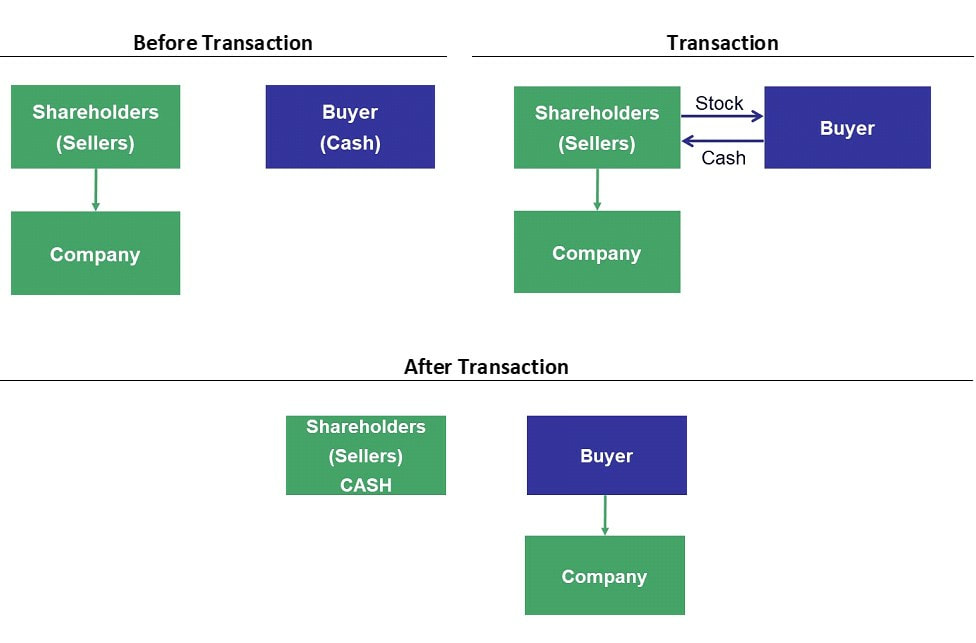

A stock-for-cash transaction is by far the most common scenario for the sale of private equity portfolio company. In a stock-for-cash transaction, a portfolio company is sold to another company and the portfolio company shareholders receive cash from the buying company in exchange for all of their shares of stock in the portfolio company. These stock-for-cash transactions can also occur in a buyout context where a buyout fund’s portfolio company acquires a smaller venture-backed company to fuel the growth of the buyout fund’s portfolio company (known as a “platform acquisition”).

What LPs Need to Know. When the fund (which is a selling shareholder) receives the cash from the buyer, the fund will typically make a distribution to its LPs of most if not all of the cash it receives from the buyer.

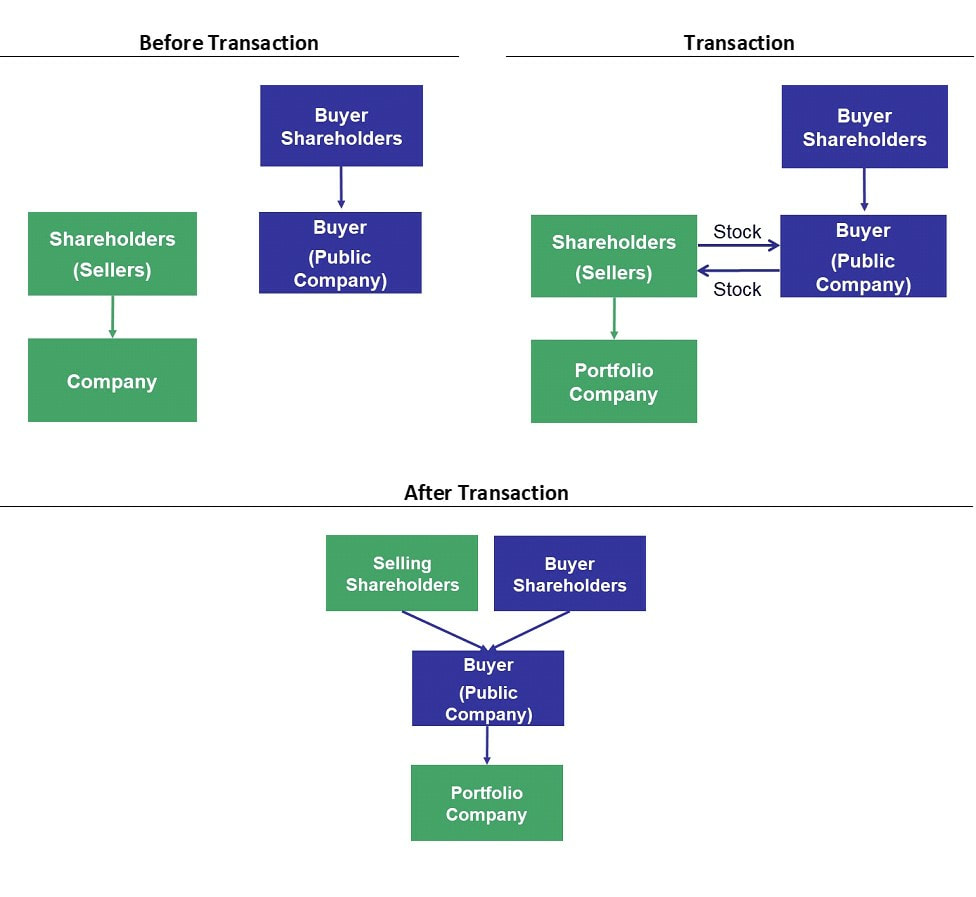

Stock for Publicly-Traded Stock

If the portfolio company of a fund is sold to a publicly-traded company, the shareholders of the portfolio company (including the fund) may receive publicly-traded stock of the buyer, or may receive a combination of publicly-traded stock and cash. These types of transactions are much less common than a pure stock-for-cash transaction discussed above.

The publicly traded stock received by the fund may be freely-tradeable, so that the fund can sell the stock on the public market for cash (and the fund would likely distribute most or all of this cash to its LPs) or distribute the freely-tradeable shares to its LPs. More likely however, is that even though the fund receives publicly-traded stock, the buyer (the public company) may impose certain restrictions on the fund, such as a “lockup restriction” where the fund cannot sell the stock for a period of time, usually 6 months. This lockup restriction is imposed so that the shares issued in the transaction won’t be sold on the stock market immediately which could drive the stock price down, and so the market has time to digest the fact that the shares will be sold into the market after the lockup expires. In this case, the fund will likely hold these restricted securities until the restrictions expire, and then may sell the stock or distribute the stock to the LPs.

What LPs Need to Know. When a stock-for-public-stock transaction occurs, if the stock received by the fund is freely tradeable, the fund may sell the stock and distribute most or all of the proceeds to the LPs, or the fund may distribute the freely-tradeable stock to the LPs. If the stock is subject to restrictions, the fund will usually hold on to the stock until the restrictions expire, and then will either sell the stock and distribute most or all of the proceeds to the LPs or simply distribute the now freely-tradeable stock to the LPs. What all this practically means for an LP is that if a fund announces the sale of a portfolio company in exchange for publicly-traded stock, the LP should ask the GP about any restrictions (and the duration of the restrictions) on the securities.

Stock for Privately-Traded Stock

Less common is a sale of a portfolio company in a stock for stock transaction where the buyer is a privately-held company. Recall that stock of a privately held company is “restricted stock” in because there is no public market where the stock can be sold, and there are likely other restrictions on sale or transfer of the stock (which are contained in a stockholder agreement).

What LPs Need to Know. A stock-for-private stock transaction is not a “liquidity event” for a fund or its LPs. Practically speaking, all that occurs in these transactions is that the fund will now own shares of a different private company, which now becomes a portfolio company of the fund. The fund will hold these shares until a “true” liquidity event occurs.

Side note. Many limited partnership agreements (“LPAs”) prohibit a fund from distributing privately-held stock to the LPs. This is for practical reasons – most LPs don’t want to receive privately-held stock from the fund, due to the administrative burden and holding costs that the LP would incur. Also, the fund is in the best position to liquidate its holdings in a private company in order to maximize returns. While LPAs prohibit the distribution of restricted stock to LPs, most LPAs do allow the fund to distribute publicly-tradeable securities to LPs.

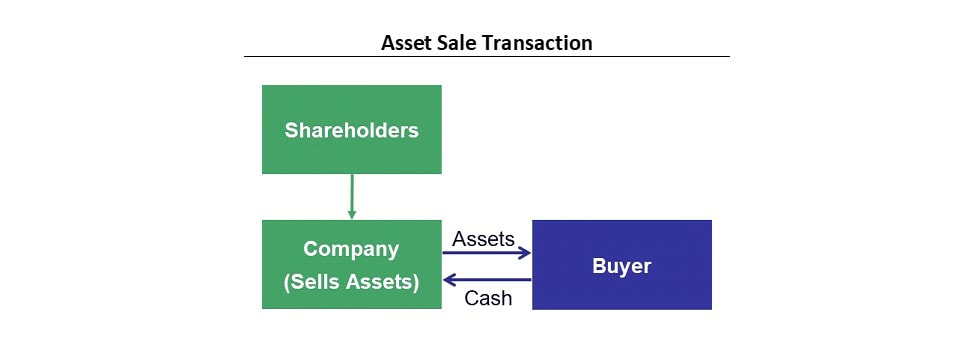

Asset Sales

Another popular way to structure the purchase/sale of a portfolio company is an asset sale. In an asset sale, the buyer acquires the assets of the selling company in exchange for cash. There are many legal and tax reasons why asset sales are favored by buyers.

What LPs Need to Know. In an asset transaction, it can take time for the portfolio company to pay off its creditors and to wind down. This means that the fund may not receive cash from the transaction for many months. When an asset transaction occurs, the fund will ultimately receive cash, most or all of which will be distributed to the LPs.

Mergers

Mergers occur when two companies merge together to create one combined company. Mergers often occur when the two companies are roughly the same size. The senior management of the merged entity contains some of the senior managers from each of the two separate companies. In contrast, an acquisition is where one company acquires another (or its assets), and owns the acquired company (or its assets). The acquiring company is usually larger than the acquired company, and the acquiring company (the buyer) determines which, if any, of the acquired company’s senior management stays or goes.

Practically speaking, in private equity, most mergers occur between two privately held portfolio companies. This means that the shareholders (including a fund) of the two separate entities end up with privately-held stock of the new, merged entity. This means that a merger of two privately-held portfolio companies is not a liquidity event. The fund receiving stock of the new merged entity will treat that company as a portfolio company. It is only when the new merged entity has a true liquidity event (sale, IPO, etc.) that the fund will be able to exit the investment.

Mergers of private companies usually occur in situations similar to stock-for-privately-held-stock transactions discussed above: when two small companies in a sector merge to become a leader in the sector. As a real-life example, consider the online freelancer marketplace Upwork. Upwork was the product of a merger between two privately-held competitors Elance and oDesk. Elance was backed by venture capital firms including New Enterprise Associates and Kleiner Perkins. oDesk was backed by Benchmark, Globespan and Sigma Partners, among others. After the merger in 2014, the company rebranded to Upwork, and went public in October 2018.

What LPs Need to Know. A merger of two privately-held portfolio companies is not a liquidity event.

Other Things LPs Need to Know About Mergers & Acquisitions

Now that the basic structures and implications for LPs have been discussed, there are many nuances that LPs must understand about mergers and acquisitions.

An Announcement of a Deal Doesn’t Mean it Will Close.

If a deal is announced, the press release will indicate that a “definitive agreement” has been signed for the buyer to acquire the seller, or for the companies to merge. Entering into a definitive agreement does not mean that the transaction will close. In many transactions, there are conditions that must be fulfilled before the traction will close. When a transaction “closes” it means that all conditions have been met, and the transaction is completed. Common conditions to closing (known as “closing conditions”) include receiving any required regulatory approvals (such as the transfer of a license), obtaining necessary consents from third parties (such as the consent of the seller’s landlord to the buyer assuming the lease), and the clearance of anti-trust hurdles (this occurs in larger deals where the parties make certain filings with the government so that the government can evaluate whether the transaction would negatively impact the marketplace due to elimination of competition – such as creating a monopoly).

The time from signing a definitive agreement to closing can be relatively short, from a month or two, to relatively long, six months to a year. When a deal closes, the buyer will usually issue a press release indicating that the transaction has closed. The bottom line for LPs is that if there is a press release of a “definitive agreement” it does not mean that the deal has closed, and the LP should monitor the situation.

Escrows

When a buyer acquires a company (whether in a stock purchase or asset purchase), it is common for the buyer to require provisions to protect it from surprises (such as unexpected liabilities) after the deal closes. This is the purpose of what is known as a “holdback escrow” or simply “escrow.” An escrow account is established, usually with an escrow company or a bank that specializes in these escrows. At the closing of the transaction, a portion of the purchase price (typically 5% to 15%, but it can be more or less depending on the transaction) is deposited into the escrow account for a period of time (typically 12 to 18 months, but it can be shorter or longer). If there is a problem, the buyer will make a claim against the escrow to cover any damages the buyer has suffered. For an LP, escrows mean that a portion of the purchase price is being held back. Funds will account for escrows in different ways, but it is common for a fund to report an escrow on its financial statements as a separate line item and to take a discount to the amount of the escrow to reflect the uncertainty of payment.

Earnouts

Another common feature of acquisitions is an earn-out. An earnout is a future payment or payments by the buyer to the seller based upon the performance of the acquired company after it is acquired. Earnouts are often used to bridge the purchase price expectations of the seller with those of the buyer. A buyer may be willing to pay additional sums to the seller if the company performs well after the acquisition. For example, let’s say that management of a company thinks the company is worth $100 million while the buyer thinks the company is worth $80 million. An acquisition could be structured so that the buyer pays $100 million as follows: $70 million up-front, with $10 million held back in an escrow, and $20 million in earnout payments if the company meets certain cash flow (or revenue, or EBITDA, or other) metrics over the next two years. The accounting for earnouts is complicated, and so LPs must understand how a fund accounts for earnouts as well as the terms of the earnout and likelihood of payment.

The Announced Purchase Price May Not Be What Is Actually Paid

Because of the use of escrows and earn-outs, the announced price may not be the actual price paid by the buyer in an acquisition. If the buyer makes claims against an escrow, or earnout payments are not met, then the announced purchase price may not be realized. When an announcement is made regarding an acquisition of a portfolio company, the LP must dig in to really understand the terms of the deal, including conditions to closing, escrows and earnouts.

As an example, assume that ABC Fund owns 100% of the outstanding shares of portfolio company Targetco. A press release is made as follows: “Targetco has entered into a definitive agreement to be acquired by Bigco for $100 million.” Based only on this statement, we know that because a definitive agreement has been signed there are conditions to closing, and so the deal has not closed. We know nothing about the structure of the transaction or the escrows or earnouts that may be in place. An LP would need more information from the fund to be able to understand the likelihood of the deal closing, the amount paid at the closing, the amounts held back in an escrow, and whether any earnout exists. With this information, an LP can better assess when it might obtain a distribution and how much it might be.

***

Please help me improve this post - your input would be greatly appreciated. You can either comment on the post or contact me via the contact page. I will update this post periodically. Thanks.

© 2019 Allen J. Latta. All rights reserved.