- LP Corner: Private Equity Fund Performance – An Overview - This blog post.

- LP Corner: Fund Performance Metrics – Multiples TVPI, DPI and RVPI

- LP Corner: Fund Performance Metrics – Internal Rate of Return (IRR) – Part One

- LP Corner: Fund Performance Metrics – Internal Rate of Return (IRR) – Part Two

- LP Corner: Fund Performance Metrics – Public Market Equivalent (PME)

- LP Corner: Fund Performance Metrics - Private Equity Fund Performance

- LP Corner: Gross vs Net Returns

Introduction

How do LPs measure performance of a private equity fund? It’s not a simple as one would think. This post introduces a number of concepts, each of which will be discussed in more detail in future posts.

The following are the basic metrics used to evaluate fund performance:

- Rate of return. This is also called internal rate of return, or IRR.

- Multiples. These multiples include Total Value to Paid-in-Capital, Distributions to Paid-in-Capital, and Residual Value to Paid-in-Capital.

- Relative performance. This is performance relative to comparable funds (also called quartile performance).

- Public market equivalent performance. This is known as PME, and has a number of variants.

Each of the above performance metrics have positives and negatives.

To read more, please click on "Read More" to the right below.

Three other concepts to introduce:

- Vintage year. The vintage year of a fund is the year the fund was formed. The “vintage” reference is an analogy to fine wines, where a particular vintage year may result in some spectacular wines. A fund’s vintage year is used in the relative performance metrics, as funds of the same vintage year and strategy are compared to one another. But what is the year of “formation”? Is it the year the fund was legally formed? The year the first investment was made? The year of the initial capital call from LPs? In my view, the vintage year should be based on the year of the initial capital call from LPs. The reason for this is it is only when a fund calls capital from its LPs does the clock start ticking for measuring an LP’s IRR for the fund.

- Interim performance vs final performance. Private equity funds have fund terms of anywhere from seven to thirteen years, but often have a few residual investments that take longer to realize. Final performance is the performance of the fund after all investments have been realized, all distributions have been made to the limited partners, and the fund is fully liquidated. Only final returns provide completely accurate performance metrics for a fund. Interim returns are just that – returns of the fund while it is actively making and/or realizing investments. Interim returns early in a fund’s life (the first two to three years) are notoriously inaccurate, and so must be viewed with a large grain of salt. It is only after five to seven years that a fund’s returns tend to stabilize and be decent predictors of a fund’s final returns.

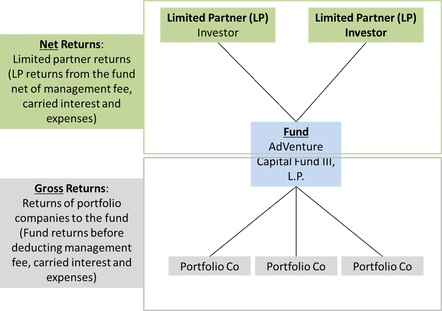

- Gross vs net returns. What LPs care about are net returns. Net returns are the returns to the LP net of all fund management fees, carried interest and fund expenses. Gross returns are the returns the fund has from portfolio company investments, but excludes the impact of fund management fees, carried interest and fund expenses.

The chart above illustrates gross vs. net returns. Gross returns are always greater than net returns. The reason this is highlighted is new managers that don’t have a prior fund performance to point to may sometimes use some personal investments a track record and provide the gross returns and hope that unknowing LPs will invest on the basis of these gross returns. Other may use the gross performance and “net out” hypothetical management fee and carried interest to arrive at a “net” number. For a more in-depth discussion of gross vs net returns, please see my post LP Corner: Gross vs Net Returns.

Here’s a question for you: My fund has an IRR of 23%. Is this good or bad?

Before answering, you should ask a few questions:

- Is this a gross IRR or a net IRR? Important because if it’s a gross IRR, the net IRR will be less (and can be meaningfully less).

- What is the fund’s vintage year? (another way of asking how old is the fund?). If the vintage year is very recent - 2 to 3 years old, then the IRR is likely to change meaningfully over time.

- What is the fund’s strategy? The fund's strategy (venture, growth, buyout, distressed debt) will also affect the analysis.

© 2018 Allen J. Latta. All rights reserved.