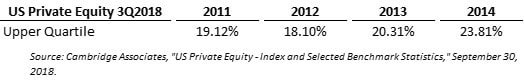

Consider the following hypothetical: In 2011, two private equity professionals decide to raise a fund. That year they form a legal entity for the fund and launch their fundraising efforts. In late 2012 the fund has its initial closing of commitments from limited partners, and makes its first capital call, where limited partners make their first cash contribution to the fund. In 2013, the fund makes its first investment. In 2014, the fund has its final closing. As of September 30, 2018, the fund has a net IRR of 18.5%. What should the vintage year be for this fund - 2011, 2012, 2013 or 2014?

To read more, please click on "Read More" below.

There are several options for what a private equity fund’s vintage year could be:

- The year when the fund was legally formed

- The year when the fund has its initial closing (of limited partner commitments)

- The year of the first capital call from limited partners

- The year of the fund’s initial investment

- The year of the fund’s final closing

- The year that the fund manager says it is

Industry participants use one (or more) of the above to determine vintage year. But which definition is right? Or is there more than one possible definition?

Let’s first start by exploring a fund’s timeline of its early activities:

Timeline - Normal Fund

Legal Formation. When is a fund legally formed? Usually not until the manager is highly confident that they will have an initial closing. This is because of the legal costs involved in forming the entity and preparing the limited partnership agreement. If you want to determine the date of legal formation for a fund, you can find it in the limited partnership agreement or in the footnotes to the fund’s audited financial statements. If you’re not an investor of the fund, most US private equity funds are formed as Delaware limited partnerships, so you can go to the entity name search page of the State of Delaware website to look up the fund. The entity name search webpage can be found here: https://icis.corp.delaware.gov/Ecorp/EntitySearch/NameSearch.aspx. This is the only date for which there will likely be a public record. For the rest of the dates, you will need to be a limited partner to obtain the information, unless the fund has made a public announcement.

Initial Closing. In a normal situation, a fund will have an initial closing of limited partner commitments a relatively short period of time after the fund has been legally formed. The initial closing occurs when limited partners sign the limited partnership agreement, which legally binds them to providing the fund with capital. It’s called an “initial closing” as most limited partnership agreements allow the fund manager to continue to raise capital for a year after the initial closing. Within that one-year period, when the fund reaches its target fund size (or “hard cap” on the fund size), it will have its final closing, after which the fund will no longer accept new investors.

Initial Capital Call. Usually, at the time of the initial closing, or very soon after, the fund will make its first capital call from investors. A capital call occurs when a fund sends a notice to its limited partners that they must provide it with the amount of money specified in the capital call, usually within 10 business days after the notice. The initial capital call is very important to the fund manager, as the fund manager may have been advancing all of the fundraising expenses (travel, legal, etc.) prior to the closing of the fund, and once the fund receives the initial capital call, the fund can pay for all of these the organizational expenses. In addition to paying the organizational expenses, the proceeds for the initial capital call will be used to start paying the management fee and for initial investments.

The initial capital call is also an important date for the fund and LPs from a return perspective. The date of the initial capital call is the date the clock starts running for calculating the fund’s rate of return from the LP’s perspective. Recall that there are two types of returns for a fund – gross, or portfolio level returns, and net, or fund (or LP) level returns. For a discussion on gross vs. net returns, please see my blog post here: http://www.allenlatta.com/allens-blog/lp-corner-gross-vs-net-returns

First Investment. After the fund receives the capital from its limited partners from the first capital call, it will make its first investment. The first investment can be very soon after the initial capital call, or can be months (or longer) after the initial capital call. It all depends on what deals the fund has on tap and how quickly they close.

Like the initial capital call, the first investment is an important date for the fund and LPs from a return perspective. In this case the date of the first investment starts the clock running for the portfolio-level (gross) returns.

Final Closing. As mentioned earlier, most limited partnership agreements allow the fund to continue to fundraise for a year after the initial closing. Once the fund has a final closing, the fund can no longer accept new investors unless they seek and obtain approval from the limited partners.

The above timeline was for a “normal” fund. Below is one of many possible variations, which occurs when there are warehoused investments.

Timeline - Warehoused investments

Dry Closing. A fund may hold a “dry closing” for a fund. A dry closing occurs when the fund manager raises a fund, but can’t (or won’t) deploy it right away, usually because they are still investing the current fund. Most limited partnership agreements have a prohibition against deploying a new fund until 70% of the existing fund’s committed capital has been invested, used for expenses or is reserved for follow-on investments.

Okay, now that we understand some of the timing of a fund’s operations, let’s see how the various definitions of vintage year work.

The Year of Legal Formation

Overview. This is how at least one leading industry participant defines vintage year. In our hypothetical, this would be 2011.

Pros. The vintage year is easy to determine from the fund’s LPA or audited financial statements, or if the fund is a Delaware limited partnership, the information can be found on the State of Delaware website. The date of legal formation is also a logical date to use as most funds are formed a short period of time prior to a fund’s initial closing of capital commitments from limited partners.

Cons: The date of legal formation doesn’t necessarily correlate to date the fund starts its operations, such as calling capital from limited partners or making investments in companies. In addition, in some (rare) cases, the legal formation date of a fund may occur well before the fund has its initial closing. For example, what if a first-time manager legally forms the fund in 2018, but doesn’t have an initial closing on the fund until 2020?

The Year of the Fund’s Initial Closing

Overview. The date of the fund’s initial closing is a legal event and is the day the fund has the contractual right to call the committed capital from investors. Note that if it’s a dry close, then even though the fund manager has the right to call capital, it can’t (or won’t) for a period of time. If the fund has warehoused investments, then these investments will generally transfer over to the fund at the time of the initial closing. In our hypothetical, this would be 2012.

Pros: It’s the legal date the fund has the right to call capital. It is usually (but not always) the same date as (or within a couple of days of) the initial capital call.

Cons: As stated above, the date of the initial closing is not necessarily the same date that operations start. That is usually the date of the initial capital call. Also, the initial closing may not be close in time to the initial investment (which may have been warehoused prior to the initial close).

The Year of the Fund’s Initial Capital Call

Overview. The date of the fund’s initial capital call is the first time that limited partners have to give money to the fund. This is the date that the clock starts for LPs to measure the fund’s net IRR (fund-level IRR). This is a key date, similar to the date of the fund’s first investment. Once the fund receives the funds from the first capital call, the fund will pay its organizational expenses, start paying management fee and can start investing. In our hypothetical, this would be 2012.

Pros: From an LP’s perspective, the initial capital call is the first date that the LP has contributed cash to the fund. It’s also the starting date for measuring the LP’s cash flows to and from the fund, which provides the LP’s rate of return (IRR) for the fund.

Cons: If the fund has warehoused investments, then the date of the initial capital call may be many months after the date the fund’s initial investment was made.

The Year of the Fund’s Initial Investment

Overview. Many industry participants define vintage year as the year of the fund’s initial investment. This makes logical sense as it is the first date of the fund’s investment activity. It also is the start date for analyzing a fund’s portfolio-level cash flows and calculating a fund’s gross portfolio returns (Gross IRR). In our hypothetical, because the fund warehoused investments, this would be 2013.

Pros. Using the date of the fund’s first investment makes sense as it is the time of the fund’s first real operational activity – namely its first investment. It is also the start date for calculating a fund’s gross (portfolio-level) internal rate of return (IRR). If the fund has warehoused investments, this date will be prior to the initial closing date for the fund.

Cons. The date of the first investment can be very different than the fund’s initial closing or its initial capital call. As discussed above, if principals of a firm warehouse investments in anticipation of their new fund, the date of first investment can be before the date the fund is legally formed, sometimes by a long time. Also, if the fund has warehoused investments, these investments may not reflect the real investment pace that the fund will have after it calls capital.

The Year of the Fund’s Final Closing

Overview. The year of the fund’s final closing can vary widely. Some funds have single closings – meaning that the fund’s initial closing is also its final closing. For other funds, the final closing can take place 12 months (or longer) after the initial closing. In our hypothetical, this would be 2014.

Pros: It’s the date that the fund stops fundraising and devotes all of its time to investment activities (and of course planning for the next fund!).

Cons: The year of the final closing has no relationship to the fund’s legal formation, commencement of operations, investing activities or calling capital from LPs.

The Year the Fund Manager Says It Is

Overview. Most fund managers will decide or advocate the vintage year for their fund. It will usually be one of the years discussed above.

Pros: The fund manager may be the best positioned to really understand when the fund really “begins.”

Cons: The fund manager may consciously or unconsciously choose a vintage year for their fund that portrays the fund in the best light for comparative industry returns. For example, if a fund had its initial capital call in late 2015 but made its first investment in 2016, it could be argued that it is a 2015 or 2016 vintage fund. If the fund is a top quartile performer when identified as a 2015 vintage fund but a second quartile performer when identified as a 2016 vintage fund, the manager may advocate for the fund to be identified as a 2015 vintage fund.

A Survey of How Industry Participants Define Vintage Year

Institutional Limited Partners Association (ILPA)

https://ilpa.org/

The ILPA has a glossary of terms, which can be found here: https://ilpa.org/private-equity-glossary/. The ILPA defines vintage year as follows:

“The year of fund formation and/or its first takedown of capital. By placing a fund into an particular vintage year, the Limited Partner can compare the performance of a given fund with all other similar types of funds form in that particular year.”

CFA Institute - Global Investment Performance Standards

https://www.gipsstandards.org/Pages/index.aspx

The CFA Institute’s Global Investment Performance Standards, or GIPS, defines vintage year as follows:

“Two methods used to determine vintage year are:

1. the year of the investment vehicle’s first drawdown or capital call from its investors; or

2. the year when the first committed capital from outside investors is closed and legally binding.” (see Global Investment Performance Standards (GIPS®) 2010).

Cambridge Associates

https://www.cambridgeassociates.com/

The highly regarded private equity consulting firm Cambridge Associates defines vintage year as follows:

“[T]he legal inception date as noted in a fund's financial statement. This date can usually be found in the first note to the audited financial statements and is prior to the first close or capital call.” (See, Cambridge Associates, “US Private Equity Index and Selected Benchmark Statistics” September 30, 2018).

Pitchbook

https://pitchbook.com/

Private equity data firm Pitchbook defines vintage year as follows:

“The vintage year is assigned by: 1) year of first investment; 2) if year of first investment is unknown, then year of final close; or 3) if firm publicly declares via press release or a notice on their website a fund to be of a particular vintage different than either of the first conditions, in which case the firm’s classification takes precedence.” (See Pitchbook, “Global PE & VC Fund Performance Report,” Data through 1Q2018).

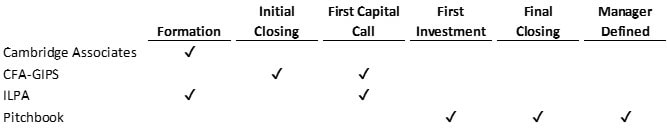

Here’s a chart summarizing the above:

Final Comments

In my view, from the LP perspective, the best metric for vintage year is the year of the fund's initial capital call. This is because this starts the clock for Net IRR, which is what LPs use to measure the performance of a fund. This is followed closely by the year of initial investment, which starts the clock for Gross IRR, which is what is used to measure the performance of the fund's portfolio investments. To me, the other options don't really relate to the fundamental activities of the fund - calling capital from LPs and investing that capital into companies.

Why does vintage year matter? As we saw with the hypothetical, it matters because a fund’s returns are compared to other funds in its vintage year. If a fund is not identified with the correct vintage year, it could overstate or understate the fund’s performance relative to its peers.

In my view, LPs need to carefully analyze each fund and determine for itself what vintage year the fund should be.

© 2019 Allen J. Latta. All rights reserved.