When an investor makes an investment in a mutual fund, the investor invests the entire amount of the investment on day 1. The mutual fund manager will quickly use this money to increase existing positions in the fund or make new investments. It’s easy for the mutual fund manager to put the money to work by buying publicly-traded securities.

Investments in private equity funds are different. Private equity funds operate on a “called capital” model. By way of background, when an investor (known as a “limited partner” or “LP”) makes a legal commitment to a private equity fund, the LP commits to providing the fund with a certain maximum investment amount, which is known as the “LP commitment.” For example, if an LP agrees to invest a total of $10 million in a private equity fund, that $10 million is the LP commitment. For more background, please see the following posts:

- LP Corner: On Committed Capital, Called Capital and Uncalled Capital

- LP Corner: US Private Equity Fund Structure – The Limited Partnership

To read more, please click “Read More” below.

Example. Let’s say that ABC Fund has received $100 million in total LP commitments and that XYZ Foundation has committed $5 million to the fund. XYZ’s total capital commitment is $5 million. At the closing of the fund, ABC Fund calls 10% of the total commitment from each LP (called a “10% capital call”). As XYZ Foundation has committed $5 million to the fund, the 10% capital call means that XYZ Foundation must wire transfer $500,000 to ABC Fund within the time prescribed by the limited partnership agreement (capital calls are usually required to be made on 10 business days’ notice). Assuming all LPs honor the capital call notice, then ABC Fund will receive a total of $10 million from all of its LPs.

So back to the question: Why does a private equity fund call capital over time instead of taking all of the capital up front on day 1 like a mutual fund?

The simple answer is that private equity firms and funds are sized and structured so that the investment team will identify and make investments over an “investment period” that usually lasts 5 years. The investment team is constantly sourcing, evaluating and making investments. This process occurs over the entire investment period. This means the fund doesn’t need all of the capital up front, and so the fund only calls capital when it needs it, such as when it is ready to make an investment, or to pay management fees or fund expenses. This is why private equity funds call capital over time.

Cash Drag

But there’s another side to this, and it is known as “cash drag.” Cash drag is the negative impact on a fund’s performance that is caused by having too much cash on the fund’s balance sheet.

Example. To understand this, let’s continue to use our example. ABC Fund has capital commitments of $100 million. To make this example easy, we will assume that ABC Fund has no management fee or carry and makes four investments of $25 million each in one-year intervals. Also assume that at the end of year 5 the fund sells all of its investments for $300 million and returns all of this $300 million to the limited partners.

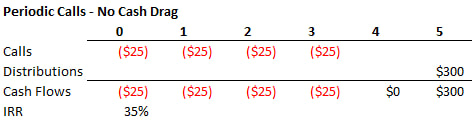

Assuming the fund calls the capital when it makes each investment, the cash flows to/from the LPs would be as follows:

Based on the above cash flows, the IRR for the fund is 35%. Because the fund called the capital only when it needed it, there is no cash drag.

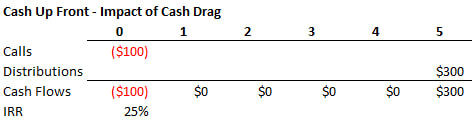

Now what if the fund called all of the capital on day 1 and kept it on its balance sheet until it needed the money for each investment. The cash flows to/from the LPs would look like this:

LP Burden

The called capital model results in an investment cost to the LP and also creates an administrative burden for the LP. Because the timing of the fund’s capital calls is uncertain and the calls are due on short notice (usually 10 business days), LPs must maintain sufficient liquidity to be able to meet these capital calls. This means that the LP must hold capital to meet near-term anticipated capital calls in investments that have higher liquidity. However, these more liquid investments typically provide lower expected returns than those for private equity funds. Because of this, some LPs may include the impact of these lower-yielding investments with the performance of the private equity funds when evaluating the overall performance of their private equity program.