Stock options provide a way for officers, directors, employees and consultants to share in the upside in the equity value of a company. Companies issue stock options to attract and retain talent, and to reward these people with upside in the company’s value. Investors in start-ups recognize the value of stock option plans, and make sure the company will have a suitable stock option plan in place to attract and retain top-level talent.

This post provides an overview of stock option plans.

To answer this, let’s first explore what options are. An option is a right to purchase an agreed number of shares of stock at an agreed price per share. For example, an option may give you the right to purchase 100 shares of common stock at $1.00 per share. If that stock rises in value to $100 per share, you would “exercise” that option by paying the company $100 (100 shares * $1.00 per share exercise price) and receive 100 shares worth $100 each, or $100,000 in total. Your profit is $99,900 ($100,000 less the $100 spent to exercise the option). That’s not a bad return!

Stock options are issued by a company to talent (an officer, director, employee or consultant) as part of a compensation package. Stock options are issued under a formal plan, called a “stock option plan” or “equity incentive plan” or something similar. These stock option plans are legal documents structured to comply with certain tax and securities laws. Stock options issued to employees (called “incentive stock options” or “ISOs”) will typically qualify for preferential tax treatment. Stock options issued to non-employees are called “non-qualified stock options” or “NQSOs” and don’t receive tax benefits.

When people talk about options, it is often said that “Bill received 1,000 options.” But what we really mean is that Bill was granted an option to purchase 1,000 shares of common stock. Stock options issued under formal stock option plans are always for common stock, which is for tax and legal reasons. You will never see a stock option plan issuing options to purchase preferred stock.

To establish a stock option plan, a company’s lawyers will draft a stock option plan, which must be approved by the company’s board of directors and stockholders. As part of this approval, the plan will authorize a maximum number of shares of stock that can be granted under the plan. This maximum number is known as the “option pool.”

The company’s board of directors authorizes grants of stock options. As part of the grant, the board will determine the number of shares of common stock underlying the option, the exercise price and the other terms of the option.

Stock Option Terms

Stock options have a number of terms, which include:

- Number of shares underlying the option.

- Exercise price of the option.

- Term of the option.

- Vesting provisions.

Let’s look at each one of these.

Number of Shares. Each stock option grant will be for a certain number of shares of common stock. For example, Betty Smith may receive an option for 10,000 shares of common stock. What’s important here is not only the number of shares, but also the percentage of the company that the shares represent. If the company has 1 million shares of stock outstanding, then the 10,000 shares of common stock underlying the option represent roughly 1% of the total equity of the company. The number of shares for the option is determined by a variety of factors including the total capitalization of the company (total shares outstanding) and the position of the person receiving the options (CEOs will get more options than others in the company).

Exercise Price. Each stock option will have an exercise price (also known as the “strike price”), which is the price per share that the person holding the option (called the “option holder” or “optionee”) would pay to exercise the option and purchase the underlying shares. Using the example from the paragraph above, if Betty’s option grant had a $0.20 per share exercise price, then Betty would write a check to the company for $2,000 to buy the 10,000 shares (10,000 shares * $0.20 per share). If each share of the company’s common stock were valued at $300 per share, then the common stock Betty receives after exercising the option would be worth $3 million. Another way to look at this is that Betty’s profit is $2,998,000, which is the value of the stock Betty receives after exercising the option ($3 million) less the amount Betty paid to obtain the shares ($2,000). If the value per share of the company’s stock is greater than the exercise price, the option is said to be “in the money.”

When a stock option grant is made, the board will set the exercise price at “fair market value.” Fair market value can be determined by the board, but most companies will have an independent valuation firm determine the fair market value of the common stock. These valuations are called “409A valuations” after the tax code that that provides for them. Companies will typically obtain a 409A valuation every year, or possibly sooner if there are material events at the company that could impact valuation, such as winning a major customer contract.

Option Term. Most options have a ten-year term. That means if the option isn’t exercised within ten years, then the option expires. An option holder will only exercise the option if it is “in the money” (the fair market value per share is greater than the exercise price). Many options will have a provision that says that if there’s value in the option at the time the option expires, then the option will automatically be exercised and common stock having a value equal to the net option value will be issued. This is known as a “net issue exercise” or “automatic exercise” provision.

Vesting. Vesting is a concept where an option holder’s right to exercise the option is conditioned upon how long the option holder is employed by the company. Stated another way, although the option holder has been granted options, the option holder only has the right to exercise a portion of the option after the option holder has remained an employee of the company for a period of time. This concept is called “vesting.” An option “vests” under a “vesting schedule.”

For example, an option can vest in 48 equal amounts over 48 months. If an employee is granted options to purchase 480 shares of common stock vesting equally over 48 months, then 10 shares vest for each month the employee stays with the company. If the employee stays for 1 year, the employee’s options will have vested for 120 shares. The remaining 360 shares is “unvested.”

When an employee leaves a company, the employee keeps all of the vested options, but forfeits any unvested options.

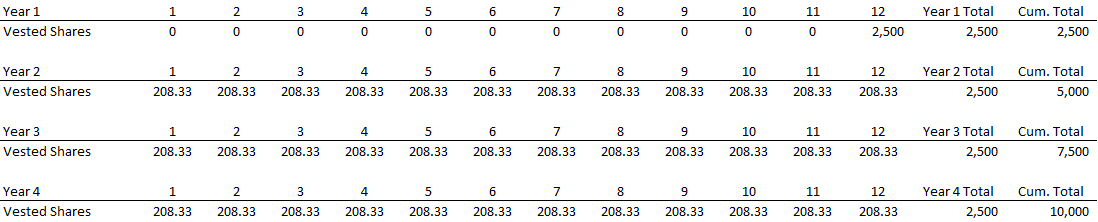

Vesting with 1 Year Cliff. Probably the most common vesting schedule is a 4-year vesting period with a one-year “cliff.” This means that no portion of the option vests for one year, at which time 25% of the option vests and is then exercisable. Then the remaining unvested portion of the option vests over the next three years. The table below shows this vesting schedule for an option grant of 10,000 shares.

Stock Option Plans

When a company adopts a stock option plan, the plan will provide for a maximum number of shares that can be granted under the plan. The legal/technical term is that the plan “authorizes” a maximum number of shares under the stock option plan. For example, a stock option plan may authorize 100,000 shares of common stock to be issued under the plan. When the company issues all 100,000 shares, the company can’t issue any more until the plan is “refreshed” by increasing the authorized number of shares. The authorized number of shares under a plan is also known as the “option pool.”

When a company adopts or refreshes a stock option plan, existing investors are diluted. This means that the ownership interest of existing investors will be diluted by the number of options that are granted and exercised. For more on dilution, see the posts “Anti-Dilution Protection: An Overview,” “Dilution Part One: Understanding Ownership Dilution,” and “Dilution Part Two: Value Dilution.”

Size of Option Pool

The size of an option pool will depend on a variety of factors, but in broad strokes, an option pool will usually be between 10% and 20% of the fully-diluted equity of a company. Factors that impact the size of the option pool include the size and stage of the company, the company’s hiring plans, and the skill levels of the company’s employees.

Cap Table Impact

Stock option plans will appear on a company’s capitalization table. Typically, the total size of the option pool is included in the cap table. Let’s see how this works.

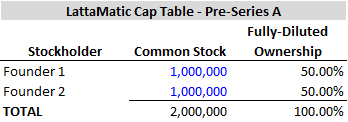

Here’s a cap table for LattaMatic before its Series A Preferred Stock financing:

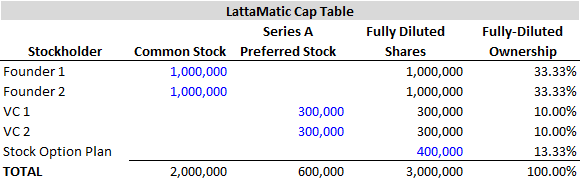

Now the company holds its Series A financing, where it raises $1.2 million by selling 600,000 shares of Series A Preferred Stock to two venture capital funds for 20% of the company. As part of the financing, the VCs require the company to establish a stock option plan with 400,000 authorized shares.

The LattaMatic stock option plan represents 13.33% of the company’s fully-diluted capitalization.

One note here is that because the VCs indicated that they would own 20% of the company post-financing, this means that the founders suffer all of the dilution from establishing the stock option pool. As a founder, you recognize the need for a stock option plan, but you want to make the stock option pool as small as possible while still meeting the company’s hiring needs.

Also note that because the VCs acquired 20% of the fully-diluted equity of company on a post-financing basis for $1.2 million, this means the post-Series A valuation of the company is $6 million ($1.2 million / 20%). This then means the pre-money valuation is $4.8 million ($6 million - $1.2 million).

When companies hold financing rounds, it is customary to refresh the stock option pool, and new investors will want the existing investors to suffer the dilution from this refresh.

Like it! If you liked this post, please give it a Like!

© Allen J. Latta. All rights reserved.