When private companies hold financing rounds with venture capital and other professional investors, these investors acquire convertible preferred stock from the company. The “convertible” or “conversion” feature of the preferred stock is fundamental to many of the rights, privileges and preferences granted to the preferred stock investors.

So what is the convertible feature of convertible preferred stock? Read on.

The “convertible” of convertible preferred stock refers to situations where the preferred stock will convert into common stock. This is important to understand because it potentially impacts a number of other terms of a preferred stock financing, such as “anti-dilution” provisions, voting provisions, dividends and more. Understanding the convertible feature is also important when working with cap tables, for discussions of “fully-diluted” capital and voting on an “as converted” basis. We’ll discuss these topics in turn.

There are two common situations where preferred stock will convert into common stock:

- Optional Conversion.

- Mandatory Conversion.

Optional Conversion

Preferred stockholders will always want the option (an option is the right, but not the obligation, to do something) to convert the preferred stock to common stock. Why? There are two main reasons:

- Money. In certain situations, such as when the company is acquired, it may be better for a preferred stock investor to convert its preferred stock into common stock. For example, a Series A preferred stock investor in the company may have its return capped at 2x the investment when a company is acquired (this is accomplished through the liquidation preference provisions, which will be discussed in a future post), but if the investor converts the Series A preferred stock to common stock, the investor may receive more than the 2x return. This will be discussed more in a future post on liquidation preference.

- Voting. Also in certain situations, typically when a state’s law requires a majority vote of both common stockholders and preferred stockholders to sell the company, the common stockholders may not want to vote for the merger if they don’t think they will receive enough money. In this case, the preferred stockholders can convert enough of their preferred stock to common stock so they then own a majority of the common stock and can vote for the merger. If this sounds unfair to the common stockholders (which are mainly the founders, early investors, and employees), it can be. This is why it is really important for entrepreneurs to fully understand the implications of the various terms granted to professional investors.

Mandatory Conversion

Preferred stockholders can be forced to convert their preferred stock to common stock in a few situations:

- IPO. When a company holds its initial public offering (IPO), it is expected that all outstanding preferred stock will convert to common stock immediately before the IPO. This is because the underwriters (the investment banks) managing the company’s IPO will require it. Public stock market investors don’t want complex equity capital structures – at most the public market will accept a Class A common stock and Class B common stock structure where the Class A common stock has a super-voting right (to keep the founders in control of the company). The public stock market investors won’t accept a company with multiple series of preferred stock that have priority over their common stock.

- Vote of Preferred Stockholders. If the holders of that series of preferred stock (such as Series A preferred stockholders) vote for it, all of the outstanding preferred stock of that series (Series A) will convert to common stock. The voting threshold for this can be a majority or some super-majority, such as a 2/3 vote.

Mechanics of Conversion

How does conversion work? It starts with the “conversion ratio” which determines the number shares of common stock each share of preferred stock converts into upon conversion. This number starts at one-to-one, or 1:1. This means that starting off each share of preferred stock converts into one share of common stock. This conversion ratio can change if certain events occur, such as a stock split, or if the company has a down round financing, known as a dilutive financing. In a dilutive financing, the “anti-dilution” provisions will change the conversion ratio for the preferred stock. For more on this, see the post “Anti-Dilution Protection: An Overview.”

“As Converted” and “Fully-Diluted” Bases

One often hears investors talk about a company’s ownership on a “fully-diluted” or an “as converted” basis. These terms assume that for purposes of the discussion all of the preferred stock is converted to common stock (it’s not actually converted, it’s just assumed to convert for the purposes of the discussion at hand).

When the term “as converted” is used, it assumes that the preferred stock is converted into common stock at the current conversion ratio.

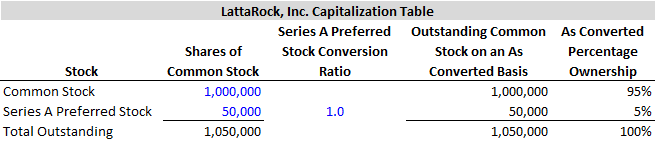

Example. Assume that LattaRock has 1 million shares of common stock outstanding, and 50,000 shares of Series A Convertible Preferred Stock outstanding which was priced at $1.00 per share and that is initially convertible to common stock on a 1:1 basis. The capitalization table (known as “cap table”) looks like this:

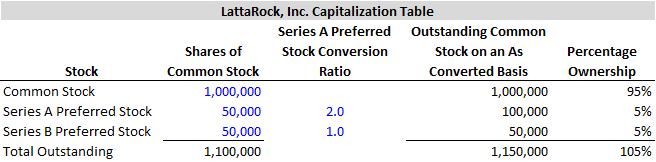

Now assume that LattaRock struggles and after some time raises a Series B round at a price of $0.50 per share, or half the price of the Series A stock. Because of the ratchet anti-dilution provisions held by the Series A Preferred stockholders, the Series A conversion ratio automatically changes to a 2:1 ratio – each share of Series A Preferred Stock converts into two shares of common stock. The new cap table looks like this:

“Fully Diluted”

In the venture capital world, fully-diluted capitalization is the total capitalization of a company, including:

- All outstanding common stock;

- All outstanding preferred stock on an “as converted” basis;

- All outstanding stock options and warrants; and

- All unissued options in a stock option pool.

There’s some variation in how “fully-diluted” is defined. In the publicly-traded stock arena, there won’t be outstanding convertible preferred stock, and only “in the money” stock options and warrants are included in the calculation. The unissued options in a stock option plan are not included.

The reason the venture capital definition of “fully-diluted” is so broad is that it’s easier to understand the impact of financing rounds on the cap table and on ultimate ownership in a company.

© 2020 Allen J. Latta. All rights reserved.