In a prior post, we discussed Rights of First Offer (also known as Pre-Emptive Rights) which offer protection against ownership dilution.

This post will explore anti-dilution protections that protect against value dilution.

In prior posts we examined ownership (equity) dilution and value dilution. Those posts can be found here http://www.allenlatta.com/allens-blog/dilution-part-one-understanding-ownership-dilution and here http://www.allenlatta.com/allens-blog/dilution-part-two-value-dilution. A take-away from those posts is that ownership dilution may not be a terrible thing, if the value of your holdings increases (for example, owning a smaller piece of a much larger pie).

Rights of First Offer (Pre-Emptive Rights)

Some investors want to maintain their ownership percentage in a company. Rights of First Offer (also known as Pre-Emptive Rights) provide investors with some protection against ownership dilution. I say “some” because as discussed in the post on this topic, there are “carve-outs” to these provisions, and so investors will experience some dilution as a company grows and expands their option pool, or issue warrants to lenders or equipment lessors. The post on Rights of First Offer (also known as Pre-Emptive Rights) can be found here: http://www.allenlatta.com/allens-blog/rights-of-first-offer-aka-pre-emptive-rights-an-overview

Anti-Dilution Provisions

What are commonly known as “anti-dilution” provisions are designed to protect against value dilution. As discussed in the prior posts, value dilution occurs when the company raises capital at a pre-money valuation that is less than the post-money valuation of the prior round. For a discussion of pre-money and post-money valuation, see the post “Pre-Money and Post-Money Valuation.”

Conversion Ratio. How investors protect against value dilution is by owning convertible preferred stock that has anti-dilution provisions. The anti-dilution provision works by adjusting the conversion ratio that preferred stock converts into common stock.

The equation for the conversion ratio is:

Conversion Ratio = Original Issue Price / Conversion Price

Original Issue Price. A bit of background. When preferred stock is issued in a financing round, that round is given a name, Series A, Series B, etc. Each round of preferred stock usually has a different price per share; for example, the Series A may have a price per share of $1.00, the Series B a price of $2.00, Series C a price of $5.00, etc. Each of these prices is known as the “Original Issue Price” for that series of preferred. The Original Issue Price never changes.

Conversion Price. The Conversion Price is the key part of this equation, as it can change. Initially, the Conversion Price is equal to the Original Issue Price for that series of preferred. For example, if a Series A preferred stock financing was priced at $1.00 per share, then the Conversion Price is also $1.00. This means the initial Conversion Ratio is 1.0:

Initial Conversion Ratio = Original Issue Price / Conversion Price = $1.00 / $1.00 = 1.0.

This means at the time of the preferred stock financing, the initial conversion ratio for the series of preferred stock being issued will be 1.0. After the financing, there may be an event that triggers a change in the conversion ratio – this is principally a dilutive financing.

Dilutive Financings

When a company raises a financing round where the pre-money valuation is less than the post-money valuation of the prior round, that is a dilutive financing. For example, if a Series A round was priced at $1.00 per share, and a later Series B round was priced at $0.50 per share, then the value of the Series A stock is being diluted.

Anti-Dilution Provisions to the Rescue. Anti-dilution provisions are designed to offset value dilution. The mechanism to do this is by reducing the Conversion Price, which in turn increases the Conversion Ratio. For example, if the Series A financing was at $1.00 per share (as above), but the Series B financing was at $0.80 per share (a 20% valuation drop), then the anti-dilution provision for the Series A Preferred Stock would kick in and the Conversion Price would drop so that each share of Series A Preferred Stock would convert into more than one share of common stock.

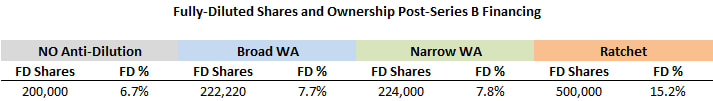

Two Types of Anti-Dilution Protection. There are two types of anti-dilution protection: ratchet or weighted average. As we will see, Ratchet Anti-Dilution is very punitive to common stockholders (including founders) and is out of favor. Weighted-Average Anti-Dilution is much more founder-friendly and is the common form of anti-dilution protection.

Ratchet Anti-Dilution

Ratchet anti-dilution is more favorable for the preferred stock investors, but it harshly penalizes all of the common stockholders. In a ratchet anti-dilution provision, the Conversion Price is reduced to the price of the dilutive financing. In the example above, the Series B is issued at $0.80 per share, which means that the Series A Conversion Price will be reduced to $0.80, and the conversion ratio would become 1.25:

New Series A Conversion Ratio = Original Issue Price / New Conversion Price = $1.00 / $0.8 = 1.25.

With a conversion ratio or 1.25, each share of Series A Preferred Stock now converts into 1.25 shares of common stock, a 25% increase from the original conversion ratio.

The other type of anti-dilution protection is weighted average, which does not increase the conversion ratio as much as ratchet. So the ratchet is more favorable to the preferred stock investors who have that right, but it significantly dilutes the common stockholders. Also, once a ratchet provision is given, future investors will also want the same protection, which could make things even worse for the common stockholders if there is a future dilutive financing. As a result, ratchet anti-dilution isn’t used that often. In their “Silicon Valley Venture Capital Survey – Second Quarter 2020” the law firm Fenwick found that there were no ratchet anti-dilution provisions used in the financings surveyed. Fenwick’s survey can be found here: https://www.fenwick.com/insights/publications/silicon-valley-venture-capital-survey-second-quarter-2020

Carve-Outs. Similar to the carve-outs in Rights of First Offer (aka Pre-Emptive Rights), certain issuances of stock, options, warrants and other securities convertible into common stock are excluded from anti-dilution provisions. Most commonly this is option grants to employees or consultants, but can also apply to warrants issued to lenders, equipment lessors, joint venture partners, technology licensors, landlords, or stock issued in connection with acquisitions.

Super-Ratchet! As a quick aside, early in my career when I was a corporate finance attorney, I worked on a venture capital transaction where the preferred stock investors negotiated a “super-ratchet” where if there was a subsequent dilutive financing the Conversion Price would adjusted to be below the price of the dilutive round. If ever triggered, this super-ratchet would effectively wipe out the common stockholders. Needless to say, a very punitive provision. I've never seen it since.

Weighted Average Anti-Dilution

Weighted-average anti-dilution provisions are not as harsh as ratchet anti-dilution, and the Conversion Price will end up somewhere between the price of the dilutive financing and the prior Conversion Price.

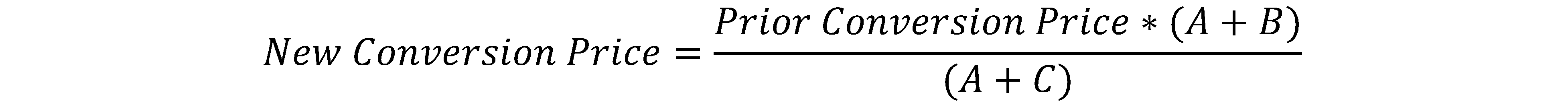

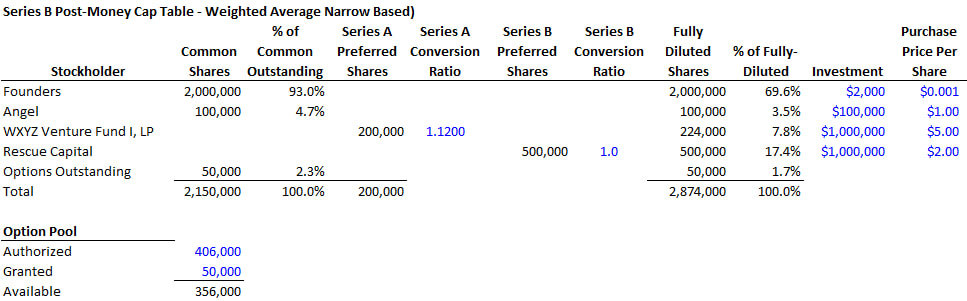

There are two types of weighted-average anti-dilution provisions: broad based and narrow-based. The most common weighted average anti-dilution formula is broad-based, and the formula is as follows:

A = Fully-diluted shares outstanding prior to the new dilutive round (in this case, fully-diluted means all outstanding common stock, plus all shares of common stock issuable upon conversion of existing preferred stock, plus all shares of common stock issuable on outstanding options and warrants)

B = the number of shares that would be issued in the new round if the purchase price per share was equal to the Prior Conversion Price

C = the number of shares issued in the dilutive financing.

Broad-Based vs Narrow-Based. Where broad-based weighted average and narrow-based weighted average differ is that broad based includes fully-diluted shares (the A input above) in the calculation where narrow-based only includes outstanding common and preferred shares and excludes issued options and warrants. By excluding options and warrants, the result is slightly more favorable to investors, but it’s usually so minimal that people just use the broad-based weighted average formula.

Bottom Line. What you need to know about weighted average anti-dilution is that it provides some protection from price dilution. Ratchet provides full protection from price dilution.

Example

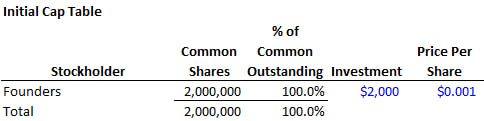

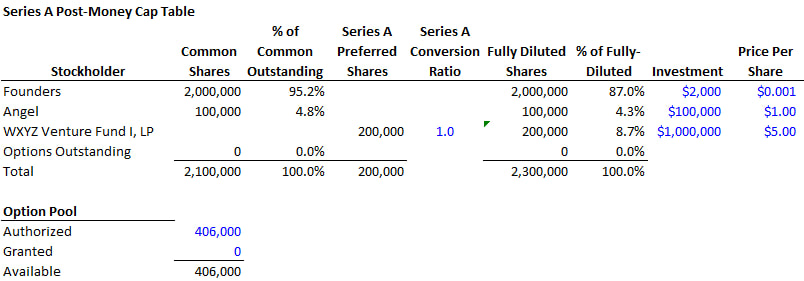

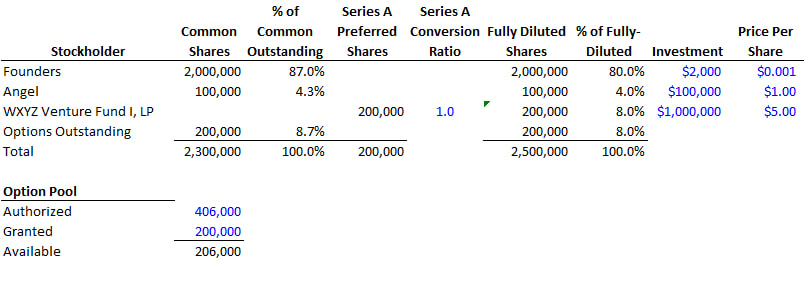

Let’s use an example to walk through this. DattaLatta, a startup data analytics company is founded by two engineers, who put up $2,000 to get the company started and issued themselves 2,000,000 shares, at $0.001 per share. (Note: Founder rounds are often priced at a very low price per share.) After the founder issuance, the capitalization of DattaLatta is as follows:

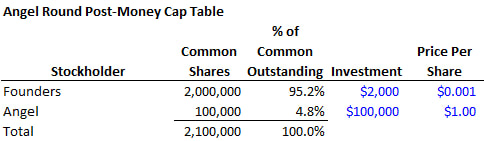

Several months later, the company has a Series A Preferred Stock financing round, where WXYZ Venture Fund I, LP (“WXYZ”) invests $1,000,000 at a price of $5.00 per share, for 200,000 shares of Series A Preferred Stock. The Series A conversion ratio is 1.0 (original issue price = $1.00 and

At the time of the Series A Preferred Stock financing, the company also established a stock option plan with 406,000 shares, which if all issued would represent 15% of the company. Immediately after the Series A financing, no options are issued.

Immediately after the Series A financing, DattaLatta’s cap table looks like this:

- Series A Preferred Shares. This shows the issuance of the 200,000 shares of Series A Preferred Stock to WXYZ Venture Fund.

- Series A Conversion Ratio. We need to calculate the fully-diluted shares outstanding, which means we need to know how many shares of common stock will be issued if/when the Series A preferred stock are converted into common stock. So we must know the conversion ratio. Here, the conversion ratio is 1.0. Recall the conversion ratio = Original Issue Price / Conversion Price. As discussed above, at issuance the initial Conversion Price is equal to the Original Issue Price, and so the conversion ratio is $1.00 / $1.00 = 1.0.

- Fully-Diluted Shares. This column shows the total shares that would be outstanding if all the preferred stock were converted into common and all outstanding options were exercised.

- Option Pool. The cap table also has added a section for the stock option pool. The company has reserved 406,000 shares of common stock for the option pool. This means the company can grant options to employees and consultants for up to 406,000 shares of common stock. These grants are made over time, usually as new employees are hired and consultants retained. As option grants are made, the "Options Outstanding" row will be updated to reflect the number of options that have been granted.

After 6 months, the company has issued options to employees for 200,000 shares. The cap table now looks like this:

Several months later, the company needs to raise additional capital, and talks to venture capital firms about investing in a Series B round. However, DattaLatta’s data analytics software is taking much longer to develop and is very buggy. In a blow, WXYZ decides not to participate in the Series B round.

Rescue Capital does invest in the company’s Series B round, and purchases 500,000 shares of Series B Preferred Stock at $2.00 per share. The $2.00 per share price of the Series B is a whopping 60% discount to the $5.00 per share paid by the Series A investor. This is a dilutive financing.

Let's see what happens in the following scenarios:

- WXYZ has no anti-dilution protection;

- WXYZ has ratchet anti-dilution protection; and

- WXYZ has weighted average anti-dilution protection.

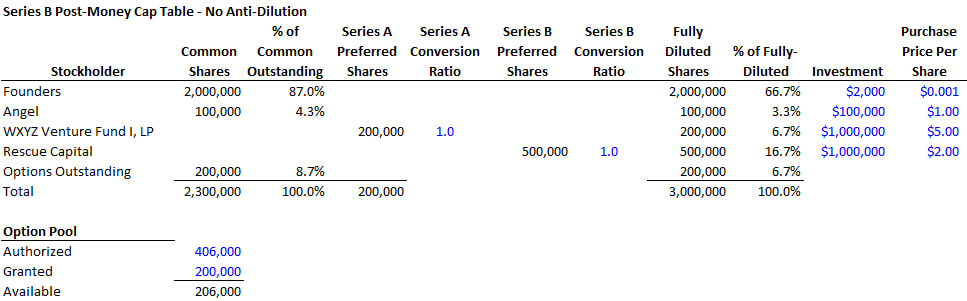

Scenario 1: No Anti-Dilution Adjustment. If WXYZ Venture Fund waives its anti-dilution protection, meaning the Series A conversion ration remains at 1.0, then the post-Series B cap table would look like this:

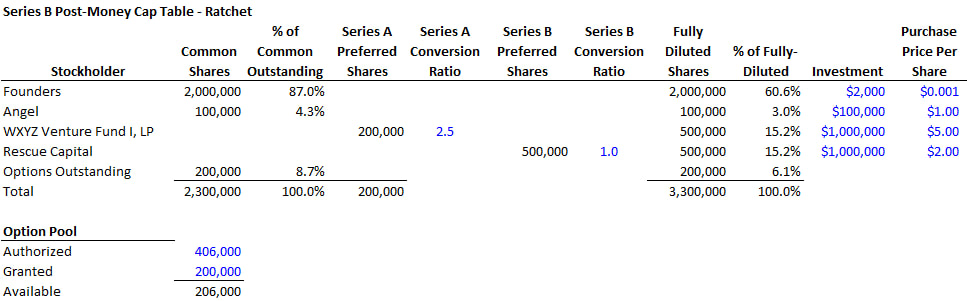

Scenario 2: Full Ratchet. Now assume that WXYZ Capital has ratchet anti-dilution protection. This means that the Series A conversion ratio will become 2.5. The math is as follows: in a ratchet, the Series A Conversion Price will equal the price of the new, dilutive financing, which is $2.00. The conversion ratio changes as follows:

New Series A Conversion Ratio: = $5.00 / $2.00 = 2.5

Plugging in 2.5 as the Series A Conversion Ratio means that WXYZ will now own 500,000 shares of common stock on a fully-diluted basis. Here’s the cap table:

- The value of WXYZ Venture Fund’s position is now $1 million dollars, which is what the value of their position was after the Series A round. The ratchet anti-dilution provision has fully protected the value of their investment.

- WXYZ Venture Fund’s ownership position on a fully-diluted basis has increased. This is how the ratchet operates. The ratchet effectively increases their ownership stake to the point where the value of their holdings remains the same. Think of it this way: a ratchet gives the investor a much larger piece of a smaller pie so that the value stays the same.

- This is a simplified example. In reality, the Series B investor would offer the company a certain amount of money for a post-closing percentage of the company. To make the model and the math easy, I’ve assumed that Rescue capital offers $1 million at $2.00 per share. Also, in a dilutive financing, the new investor would likely “top-up” the option pool to be a larger portion of the post-closing fully diluted capital.

- Finally, in my experience, if a ratchet exists, the new investor will require the old investor to either waive the ratchet, or participate in the new financing. I’ve been in a deal where the prior investor refused to waive the ratchet and the new investor walked away.

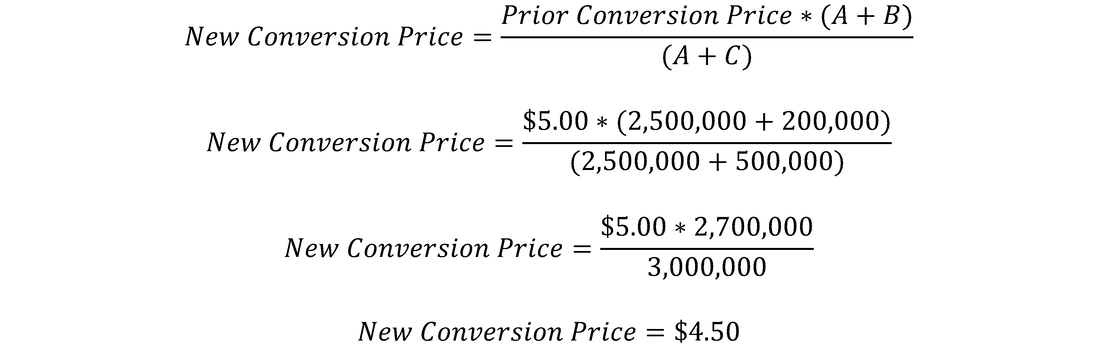

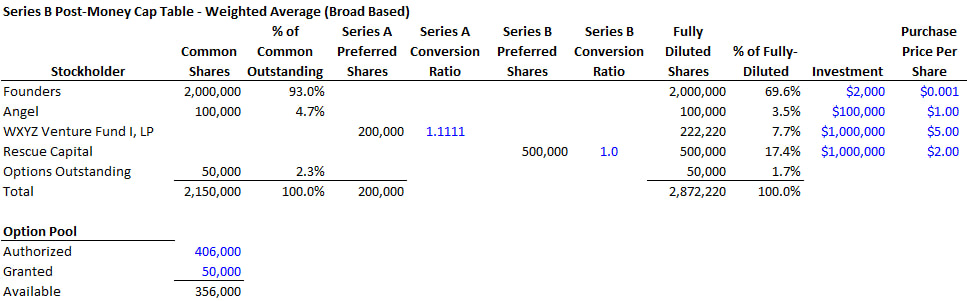

Scenario 3: Weighted Average. The most complicated has been saved for last. The weighted average will provide a result that is in between a full ratchet and no anti-dilution adjustment.

Recall the ugly weighted-average formula:

A = Fully-diluted shares outstanding prior to the new dilutive round (in this case, fully-diluted means all outstanding common stock, plus all shares of common stock issuable upon conversion of existing preferred stock, plus all shares of common stock issuable on outstanding options and warrants)

B = The number of shares that would be issued in the new round if the purchase price per share was equal to the Prior Conversion Price

C = The number of shares issued in the dilutive financing.

As a refresher, here’s the Series B pre-money cap table:

- Prior Conversion Price. Recall that the initial conversion price is equal to the Original Issue Price. This was $5.00 for the Series A preferred stock. Since there hasn’t been any adjustment since the original issuance the Original Conversion Price of $5.00 is the Prior Conversion Price. Prior Conversion Price = $5.00.

- A = The fully-diluted shares prior to the dilutive round. This is 2,500,000, from the table above. A = 2,500,000.

- B = The number of shares that would be issued in the new round if the purchase price per share was equal to the Prior Conversion Price. Rescue Capital invested $1,000,000. If the purchase price were the Prior Conversion Price of $5.00, then 200,000 shares would have been issued. B = 200,000.

- C = The number of shares issued in the dilutive financing. Rescue Capital invested $1,000,000 at $2.00 per share, for 500,000 shares of Series B Preferred Stock. C = 500,000.

Plugging these inputs to the equation:

New Series A Conversion Ratio = Original Issue Price / New Conversion Price = $5.00 / $4.50 = 1.1111.

We now plug in the new Series A Conversion Ratio into the Series B cap table as below.

So why don’t all venture capitalists require a ratchet? Because founders will not take them as investors, unless they’re absolutely desperate. Also, once a ratchet has been granted to one set of investors, all later investors will demand it, so it’s a very bad precedent. Finally, the market for anti-dilution provisions has moved away from ratchet, to the point where a ratchet is just not used in normal circumstances.

Pay-to-Play

Sometimes, if a company agrees to provide an investor with anti-dilution protection, the company will want to include a “Pay to-Play” provision, which requires the investor to participate pro-rata in the dilutive round in order for the anti-dilution protection to be effective. If the investor doesn’t participate in the dilutive round, then they can be punished by having all of their preferred stock convert into common (thus losing many of their rights and privileges), or being converted into a “phantom” series of preferred stock, where they don’t have the anti-dilution protection but keep their other preferred stock rights and privileges. According to the Fenwick report referenced above, about 6% of surveyed transactions had a pay-to-play provision in 2Q2020.

Links to other posts on dilution:

http://www.allenlatta.com/allens-blog/dilution-part-one-understanding-ownership-dilution

http://www.allenlatta.com/allens-blog/dilution-part-two-value-dilution

http://www.allenlatta.com/allens-blog/rights-of-first-offer-aka-pre-emptive-rights-an-overview

Link to the Fenwick report:

https://www.fenwick.com/insights/publications/silicon-valley-venture-capital-survey-second-quarter-2020

© 2020 Allen J. Latta. All rights reserved.