While this may sound pretty straight-forward, fund secondaries are fairly complex. One complexity relates to the fact that an investment in a private equity fund is "illiquid." It is called illiquid because it isn’t very easy for an investor in a private equity fund to sell its fund interest.

There are several reasons why interests in private equity funds are illiquid. First, unlike publicly-traded stocks which can be bought and sold very easily on public markets like the New York Stock Exchange and NASDAQ, there is no public market where one can buy or sell interests in private equity funds. Second, for stocks to be able to be sold on public markets like the New York Stock Exchange and NASDAQ, by law they must first be registered with the US Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”). Interests in private equity funds are not registered with the SEC, and so there are legal (statutory) restrictions on the sale or transfer of these fund interests. Third, investors in private equity funds sign contracts (known as “limited partnership agreements” or “LPAs”) which contain restrictions on the sale or transfer of the fund interests.

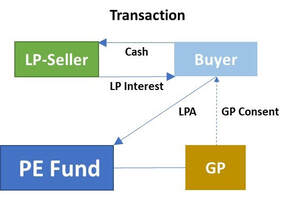

In a fund secondary transaction, a fund investor (“limited partner” or “LP”) will sell its fund interest (“limited partnership interest” or “LP interest”) to a buyer, which may be another investor in the fund, a private equity fund established for the specific purpose of buying LP interests (known as a “secondary fund” or a "secondary fund-of-fund"), some other private equity investor, or some other buyer. These buyers will work with the selling LP, the general partner of the fund (”GP”) and their lawyers to make the transaction happen. Once the sale closes, the buyer will “step in the shoes” of the selling LP, and will become an LP in the fund. This means that the buyer will be responsible to pay all future capital calls made by the fund, and will receive all future distributions from the fund.

Reasons Why a Fund Investor Will Sell Fund Interests

- Liquidity. An LP may desire or need to increase its cash and/or other short-term holdings to fund upcoming projects, to pay down liabilities, to meet capital calls of other private equity funds, to meet contractual obligations (such as bank loans that have liquidity covenants) or to improve its balance sheet.

- Reduce Future Capital Call Exposure. An investment in a PE fund is actually a “commitment” to provide the fund with capital when the PE fund needs it. This means that the GP will “call” capital from LPs on a periodic basis, and the LPs are obligated to provide that capital. In this manner, an investment in a PE fund involves both an investment and a liability – the liability being the LP’s obligation to fund future capital calls. An LP may determine that it wants to reduce its exposure to this future capital call liability, and so may sell fund interests to reduce that exposure. For more on committed capital and called capital, see the post “LP Corner: On Committed Capital, Called Capital and Uncalled Capital.”

- Portfolio Rebalancing. Most investors have an overall asset allocation strategy, with defined asset classes (stocks, bonds, cash, private equity, etc.) and investment percentage targets (usually ranges) for each asset class. So, for example, an investor may have a target allocation of 35% to 45% of the overall portfolio value in public stocks, 35% to 45% in public bonds, 2% to 5% in cash and 10% to 15% in private equity. Investors will periodically review these target allocations and if an asset class is outside the target range, the investor may adjust the portfolio by selling some investments in one (or more) asset class and buy investments in other asset classes. So, for example, if an investor has a target allocation range for private equity between 10% and 15% of the overall portfolio’s value, and private equity performs very strongly compared to other asset classes and now represents 25% of the overall portfolio value, then the investor may sell some of its private equity holdings and buy stocks and/or bonds to rebalance the portfolio.

- Change in PE Investment Strategy. Within the PE program, the investor may create target allocation ranges for certain strategies (venture, growth, buyout, private credit), geographies, sectors, ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance), etc. If one allocation exceeds the target range, the investor may use secondaries to adjust the overall PE portfolio.

- Reduce Number of Managers and/or Funds. As a private equity investment program grows, the number of funds in the investor’s portfolio grows, and the number of private equity manager relationships grows. Administering a large number of funds and manager relationships can challenge resources, and so an LP may decide to sell fund interests to reduce the number of funds and/or managers in its portfolio. Also, sometimes an LP will decide to no longer invest in a particular manager’s funds, and as a result may want to sell the legacy funds in the secondary market.

- Reduce Exposure to Tail-End Funds. A private equity fund typically has an initial ten-year term but will usually extend the term for several years, and these extensions often last for an additional two to five years or more. Funds that are ten or more years old are known as “tail-end funds.” A tail end fund may only have one or a small handful of portfolio companies left in the fund, and so these tail-end funds often have just a small amount of value left. If an LP holds many tail-end funds in its portfolio, it may decide to sell some or all of these tail-end funds as a way to reduce exposure to these older funds, or to reduce the administrative burden of managing these small investments.

- GP-Led Secondaries (Restructurings). A fairly recent development is that GPs of tail-end funds (or late in the initial 10-year term) may work with a buyer to restructure the fund. The restructuring can take many different forms, but in a basic scenario, the buyer will offer existing LPs in a fund the option to sell its interest for cash or to “stay” in the fund (which is restructured). Because the buyer is offering to buy the LP’s interest in the fund, this is a fund secondary.

- Regulatory Requirements. Changes in laws or regulations can motivate LPs to sell their interests in private equity funds. For example, the Basel III banking framework introduced after the Great Financial Crisis motivated many banks to pare back their private equity portfolios.

Reasons Why a Buyer Will Buy Fund Interests

- Attractive Potential Returns. The buyer will evaluate the LP interest that is for sale and will develop a price for the interest that the buyer thinks will generate a solid return for the buyer. If the Buyer is correct in its assumptions, secondaries can generate attractive returns for the buyer.

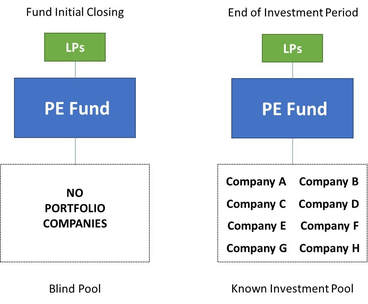

- Fund’s Investments are Known. Secondaries can occur at any point in a fund’s life, but they often occur after the fund has finished or is in the later stages of its five-year investment period. At the end of the investment period, the fund has made all of its initial investments, and so the fund’s investment portfolio is known. Compare this to a brand-new fund – at the time of the fund’s initial closing, the fund has made no investments, and so the fund’s portfolio is unknown (the fund is known as a “blind pool”). If a buyer is looking to acquire a fund interest where the fund has finished its investment period, then because the fund’s investment portfolio is known, the buyer can evaluate the fund’s investment portfolio and develop a bid price for the LP interest that’s for sale. For more on the investment period, see the post “LP Corner: The Four Phases in the Life of a Private Equity Fund.” See the graphic below:

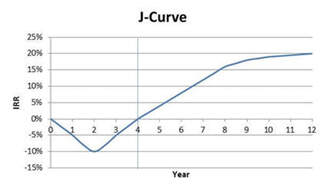

- Flatten the J-Curve. In the blog post “LP Corner: The J-Curve” we discussed how the returns for a private equity fund are typically negative in the early years of the fund as a result of organizational expenses and management fees, as well as early losses (mainly in the case of early-stage venture capital funds). In the diagram of a hypothetical J-Curve below, an LP who invests in a brand-new fund (year zero) may experience negative returns for the first few years of the fund’s life. However, by year 4 in the diagram, the early negative returns have been erased, and the fund will experience positive returns going forward. Secondary purchasers who buy an LP interest in a fund that is at least a few years old may benefit as the fund may have moved out of the J-Curve. Looking at our hypothetical diagram below, if the buyer buys a fund interest in year 4, it won’t experience negative returns and has significant upside potential. In a fund portfolio context, secondary fund purchases can help minimize, or “flatten,” the J-Curve for the entire portfolio.

- Shorter Hold Period. In a prior post, “LP Corner: The Four Phases in the Life of a Private Equity Fund,” we explored how a fund goes through phases in its life. That post also explains that even though private equity funds have initial ten-year terms, these are routinely extended, leading to funds that have lives of 15 years or more. A buyer who purchases an interest in a fund that is in years 4 or later of the fund’s life will have a much shorter holding period for this investment than if the buyer were to make commitment to a brand-new fund. A shorter hold period can be appealing to many LPs.

- Earlier Distributions. An LP that invests in a brand-new private equity fund may have to wait several years before it receives any cash back (known as “distributions”) from the fund. Because a secondary buyer buys an interest in a fund that is several years into the fund’s life, the buyer will typically receive distributions much sooner than if it had made a commitment to a brand-new fund. (For more on timing of capital calls and distributions, see the posts “LP Corner: On Committed Capital, Called Capital and Uncalled Capital” and “LP Corner: Understanding the Capital Call Model and the Impact of Cash Drag.”

- Manager Access. Some managers, notably venture capital managers, experience significant LP demand for their funds. By purchasing an interest in one of these funds, the buyer can establish a relationship with the manager and increase the chances for investing in the manager’s next fund.

Pricing

Private equity fund secondaries are usually priced as a percentage of the net asset value (referred to as “NAV”) of the fund interest being sold. Funds issue financial statements quarterly, and the NAV of the LP interest is provided with these financials (in a capital account statement). After the buyer evaluates the fund’s portfolio, the buyer will develop pricing for the LP interest being sold. If the buyer feels that the fund’s portfolio isn’t of the highest quality, the buyer may offer the selling LP pricing equal to 85% of NAV (or stated another way, the buyer will buy the LP interest at a 15% discount to NAV). In the aftermath of the Great Financial Crisis, some venture capital fund interests were being sold in secondary transactions at discounts ranging from 30% to 60% of NAV.

If, on the other hand, the buyer is very excited about the fund manager and the quality of the fund portfolio, the buyer may offer the seller a price that is a premium to NAV. A buyer would do this if they felt that the fund’s portfolio had significant upside potential.

Keep in mind that as part of the secondary transaction, the buyer “steps in the shoes” of the selling LP, and will be responsible for all future capital calls made by the fund. This means that one consideration for a secondary buyer is to understand the amount of capital calls the buyer will be responsible for in the future. The buyer will also be entitled to all future distributions made by the fund.

Example. ABC Foundation (“ABC”) is an LP in Lattaco Capital I, L.P. (“Lattaco”), a mid-market buyout fund formed in 2015. ABC committed $10 million to Lattaco, and at June 30, 2020, $7 million has been called, leaving an uncalled capital commitment of $3 million. At June 30, 2020, the NAV of ABC’s LP interest in Lattaco was valued at $12 million. XYZ Secondary Fund (“XYZ”), a private equity fund specializing in acquiring fund interests, is interested in buying ABC’s interest in Lattaco. After evaluating the Lattaco portfolio, XYZ offers ABC pricing of a 10% discount to NAV, or $10.8 million, which will include XYZ’s assumption of the uncalled capital commitment.

How Fund Secondaries Work

To understand fund secondaries better, let’s walk through the process.

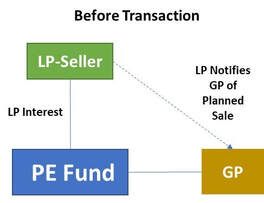

Before transaction. Before the transaction, an existing LP owns an LP interest in a private equity fund.

The LP interest is governed by the fund’s Limited Partnership Agreement (“LPA”). For more on Limited Partnership structure, see the post “LP Corner: US Private Equity Fund Structure - The Limited Partnership.” The LPA will have provisions regarding the transfer of LP interests that the selling LP must comply with in order to sell its LP interest in the fund.

The main condition is that the GP must approve the transfer of the LP interest – and the GP can approve or deny the transfer in its sole discretion. Some LPAs also contain a “Right of First Refusal” which enables the GP and/or the other LPs in the fund to buy the LP interest being sold at the price that the buyer has offered the selling LP. Other common conditions are that the selling LP provide a letter from its attorneys (called a “legal opinion”) that the transfer will comply with all applicable laws and the LPA, and won’t trigger any negative legal or tax consequences (this legal opinion requirement is often waived by the GP), and that the selling LP pay for the GP’s legal expenses incurred in reviewing and approving the transfer. Because of these provisions, the selling LP will typically notify the GP in advance that the LP is considering selling its LP interest. This is to make sure that the GP will approve the transfer, or to learn what requirements or restrictions the GP may place on the transfer.

Note that there may be reasons why the GP may not consent to a sale of an LP interest. There are legal and tax reasons why a GP may not consent to a transfer. Or the GP may not want the buyer to be an LP in the fund, or the GP may have a particular buyer in mind for a transfer. I had a situation several years ago where the GP told us that we could only sell our LP interest to one particular investor, which was not an existing LP, but had promised the GP that if it could buy the LP interest it would also invest in the next fund. This killed the deal for us as that investor knew we didn’t have any alternatives and offered pricing that simply wasn’t acceptable to us. I have also had a GP tell us that they would not approve a sale if we engaged an intermediary (known as a “placement agent”) to assist in the process, as the GP said they didn’t want any placement agent to have confidential information relating to the fund.

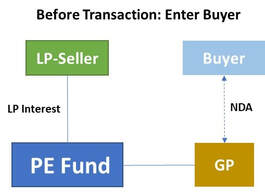

Enter Buyer. The LP gets the word out that it wants to sell its LP interest. This can happen in many different ways, but it could be through placement agent that specializes in these transactions, through the LP’s own network, or through the GP. Also, the buyer will typically want to obtain the fund’s confidential financial statements and reports. The GP must consent to providing the buyer with these confidential reports, and if the GP does consent to this, it will require the buyer to sign a non-disclosure agreement (called an “NDA”).

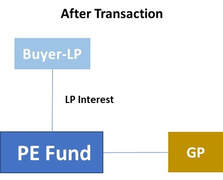

After the Transaction. After the transaction, the LP-Seller sets sail with cash in hand and no further obligation to pay capital calls, and exits the picture. The Buyer now owns the LP interest in the fund, and is responsible for all future capital calls, and will receive all future distributions.

So that’s an introduction to fund secondaries. However, this introduction just skims the surface - there’s a lot more to fund secondaries.

For example, as discussed above, the legal mechanics of the actual sale are fairly complicated. This is due to the fund’s financials only being issued quarterly (usually 45 days after the end of each quarter and 90 days after the end of a year), and the timing of capital calls and distributions.

There’s also a lot of creativity that can occur in these deals, such as structuring a fund secondary transaction as a “synthetic secondary” which transfer the economic benefits and burdens of the LP ownership interest without transferring the legal ownership of the fund interest. Buyers can also structure a payment structure where instead of paying all cash up front, the buyer will pay the seller the purchase price over time, which can improve the buyer’s internal rate of return for the transaction. An on and on. There are many possibilities when structuring fund secondary transactions.

Related Posts:

LP Corner: On Committed Capital, Called Capital and Uncalled Capital

LP Corner: Understanding the Capital Call Model and the Impact of Cash Drag

LP Corner: The J-Curve

LP Corner: The Four Phases in the Life of a Private Equity Fund

LP Corner: US Private Equity Fund Structure - The Limited Partnership

© 2020 Allen J. Latta. All rights reserved.

LP Corner® is a registered trademark of Campton Private Equity Advisors. Used with permission.