For privately-held companies, especially early-stage companies, dividends are generally not paid as these companies generally don’t have excess cash, and even if they did, they would use any excess cash to grow the company’s business. But even though dividends are generally not paid by privately-held companies, it is important to understand how dividends work because preferred stock investors may negotiate dividend provisions that could result in substantial sums of money being paid to the preferred stockholders in certain situations.

Dividends to Preferred Stockholders

When a company negotiates a preferred stock financing round, one provision that is negotiated is dividends. Preferred stock dividends come in a few basic flavors:

- No dividends.

- When and if Paid on Common.

- Non-cumulative.

- Cumulative.

Let’s look at each of these.

No Dividends. In this scenario, the preferred stockholders agree to receive no dividends at all, even if dividends are paid to holders of common stock. A term sheet might provide: “The Series A Preferred will receive no dividends.” This is very rare and not a standard term.

When and if Paid on Common. The National Venture Capital Association (“NVCA”; website: www.nvca.org) publishes a Model Term Sheet, which is a very useful tool. This term sheet can be found here: https://nvca.org/model-legal-documents/. The NVCA term sheet model language for this type of dividend is:

“Dividends will be paid on the Series A Preferred on an as converted basis when, as, and if paid on the Common Stock.”

What this is saying is that the Series A Preferred stockholders will receive dividends only when dividends are paid on the common stock, and the amount of dividends the Series A preferred stockholders will receive is calculated on an “as converted” basis. The amount of the dividend for the preferred stockholders is calculated as if all preferred stock has been converted into shares of common stock (it’s not really converted; it’s just treated that way for purposes of calculating the dividend). For a discussion of “as converted” basis, see the post “Convertible Preferred Stock: Understanding the Conversion Feature.” In this case, when dividends are paid to the preferred stockholders, the payment is made at the same time dividends are paid on the common stockholders, so there is no preferential payment of dividends to the preferred stockholders – they are treated the same as the common stockholders.

Example 1. Lattaco has 500 shares of Series A Convertible Preferred Stock and 1,000 shares of common stock outstanding. The Series A Preferred Stock converts into common stock on a 1:1 basis. Lattaco declares a dividend of $3,000 out of legally available cash. Because the Series A Preferred Stock converts on a 1:1 basis, the preferred stockholders are treated as if they own 500 common shares for purposes of calculating the dividend. The $3,000 dividend is divided by 1,500 shares (1,000 common shares and the Series A Preferred shares treated on an “as converted” basis for 500 shares) for a dividend of $2.00 per share. The Series A stockholders receive $1,000 ($2.00 per share times 500 shares on an “as converted” basis) and the common stockholders receive $2,000 ($2.00 per share times 1,000 shares of common stock outstanding.

Example 2. Assume the same facts as above, except that the Series A conversion ratio is 2:1, meaning that each share of Series A Preferred stock converts into 2 shares of common stock. In this case, the Series A Preferred would be treated as if converted into 1,000 shares of common stock. This means the dividends would be calculated on the basis of 2,000 shares (1,000 common shares and the Series A Preferred shares treated on an “as converted” basis for 1,000 shares) or $1.50 per share. The Series A Preferred stockholders would receive $1,500 in dividends and the common stockholders would receive $1,500. So the conversion ratio can impact the amount of dividends paid to both the preferred stockholders and the common stockholders.

Non-Cumulative. The non-cumulative option is described by the NVCA Model Term Sheet as follows:

“Non-cumulative dividends will be paid on the Series A Preferred in an amount equal to $[_____] per share of Series A Preferred when and if declared by the Board of Directors.”

What non-cumulative means is that if the dividends aren’t paid by the company in a given year, the dividends don’t accumulate, or accrue, and the investors have no right to any dividends. For example, if the provision above provided for a non-cumulative dividend of $1.00 per share of Series A Preferred, and over the span of 5 years the company never pays a dividend, the Series A Preferred stockholders receive nothing and aren’t entitled to anything. The opposite of this is cumulative dividends, which are described next.

Cumulative. The NVCA Model Term Sheet cumulative dividend provision is as follows:

“The Series A Preferred will carry an annual [__]% cumulative dividend [payable upon a liquidation or redemption]. For any other dividends or distributions, participation with Common Stock on an as-converted basis.”

Let’s look at the first sentence without the brackets: “The Series A Preferred will carry an annual [__]% cumulative dividend.” In this scenario, there is a defined dividend that accrues (cumulates) if it is not paid by the company. The dividend can be expressed as a dollar amount per share (such as $0.10 per share), or as a percentage of the price of the Series A Preferred (such as 8%). For example, if the Series A Preferred was sold at $1.00 per share and there is an annual 8% cumulative dividend, then each share of Series A Preferred is entitled to an annual dividend of $0.08 per share. If the dividend is not paid, it accrues, so that if a dividend is declared and paid in the next year, the Series A stockholders would receive the $0.08 dividend that wasn’t paid and so accrued plus the $0.08 dividend for the next year for a total dividend of $0.16 per Series A share.

Now let’s consider the with the bracketed language: “The Series A Preferred will carry an annual [__]% cumulative dividend payable upon a liquidation or redemption. For any other dividends or distributions, participation with Common Stock on an as-converted basis.”

What this is saying is that the cumulative dividends are only payable if there’s a “liquidation” of the company or there’s a redemption of the shares. In any other case, such as normal dividends, the Series A stock participates with the common stock on an as-converted basis.

The term “liquidation” is always defined to include an acquisition of the company, and this is where the provision is important. If the company is acquired, the “liquidation preference” will come into play and the cumulative dividends will be paid as part of this liquidation preference.

Example. Lattaco has 10,000 shares of Series A Convertible Preferred Stock outstanding, which were issued on January 1, 2020 for $100.00 per share (a $1 million investment). The Series A stock carries an annual 8% cumulative dividend, and a liquidation preference that provides if the company is sold, the Series A stock receives 2 times the Series A purchase price plus all accrued and unpaid dividends before the common stock receives any monies. The company never declares or pays any dividends. After struggling for five years, the Company is sold for $3 million dollars. The Series A stockholders receive 2x their investment plus all accrued but unpaid dividends, before the common stockholders receive any monies. This means the Series A stockholders receive $2 million (2x the $1 million investment) plus $400,000 in accrued but unpaid dividends (8% * $100 per share * 10,000 shares * 5 years = $400,000), for a total of $2.4 million. The common stockholders receive $600,000. Note that if the company were sold for less than $2.4 million, the common stockholders would receive nothing at all.

Dividends as a Component of Investment Return

Investors may require cumulative dividends as condition to investing. In this case, the investor is using dividends as a component of their expected return, and/or as a risk mitigation tool in the event the company performs poorly.

Let’s work through an example.

Lattamatic is an early stage software company. RNR ventures purchases one million shares of Series A convertible preferred stock at $1.00 per share, for a total investment of $1 million. As part of the investment, the company gives RNR an 8% cumulative dividend and a 2x liquidation preference (in this case a “liquidation” includes the sale of the company and accrued but unpaid dividends must be paid out of the sale price). Lattamatic doesn’t pay any annual dividends. The company is sold in year 7 for $3 million.

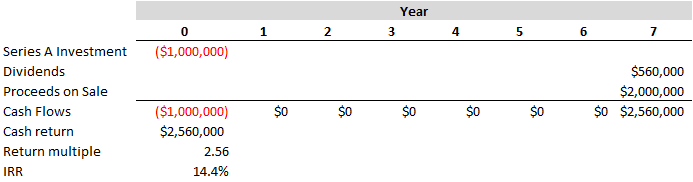

RNR’s cash flows will look like this:

Because of the cumulative dividends, RNR was to receive $80,000 per year in dividends (8% annual dividend * $1 million investment), and if the dividends weren’t paid they accumulate (accrue) and must be paid to RNR as part of a liquidation – in this case a sale of the company. Since the company didn’t pay the dividend for 7 years, there’s $560,000 in accrued but unpaid dividends. At the end of year 7, the company is sold for $3 million. Because the sale of the company is a “liquidation” at that time, RNR must receive its 2x liquidation preference of $2 million plus all accrued but unpaid dividends. This results in a cash return to RNR of $2.56 million for a 2.56x cash on cash return. It also results in an IRR of 14.4%.

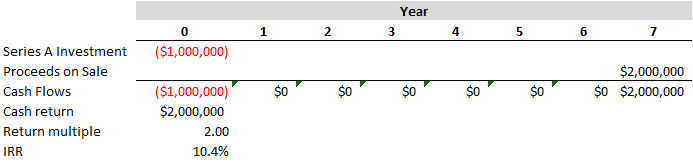

If the dividends were non-cumulative, that means that they don’t accrue, and so in that case no dividends are paid and the cash flows would look like this:

Note that whether an investor can obtain cumulative dividends depends on the negotiations with the company, and where the “market” is at that point. Generally speaking, most early-stage venture capital financing rounds do not include cumulative dividends. I sometimes see cumulative dividends in later rounds and sometimes in down round financings.

Mechanics of Dividends

To round out the discussion, let’s discuss the mechanics of a dividend. For a dividend to be paid to stockholders of a private company, there are some basic steps a company must follow:

- Board Action. The board of directors of the private company first must decide the amount of the dividend (unless this has been pre-agreed with investors, as discussed above), a “record date” which determines the stockholders who will be eligible to receive the dividend, and a “payment date” when the dividends will be paid. When the board of directors vote to pay a dividend, it is said that the board has “declared” a dividend. Once the dividend has been declared, the board will send a notice to the stockholders notifying them of the dividend, the record date and the payment date. Remember that a dividend can only be paid if the company meets the “excess cash” requirements discussed above.

- Record Date. This is the date that determines who will be paid dividends. All owners of stock at the close of business of the record date will receive the dividends. If someone buys stock after the record date but before the payment date, they are not eligible for the dividends.

- Payment Date. This is the date when the dividends are paid to the owners of stock as of the record date.

Note that the process of payment of dividends for public companies differs from the above and is a bit more complicated due to the nature of the public markets.

Basic Example. Lattaco has 100 shares of common stock outstanding. Alexandra owns 10 shares of common stock which is 10% ownership of Lattaco. On January 1, the Lattaco board declares a dividend of $1.00 per share for stockholders of record on January 31 (the record date), and the dividend will be paid on February 28 (the payment date). Alexandra owns her 10 shares on the record date and will receive $10.00 on the payment date.

Stock Dividends (PIK Dividends)

Note that companies can issue their own stock as dividends. This is known as a “Payment-in-Kind” or PIK dividend. Sometimes dividend provisions provide that the company can issue PIK dividends in lieu of cash dividends.

© Allen J. Latta. All rights reserved.